In previous sections, we explored how foundation models leverage computation through scaling laws and the bitter lesson. But how can we actually predict where AI capabilities are headed? This section introduces key forecasting methodologies that help us anticipate AI progress and prepare appropriate safety measures.

Why should we care about forecasting? Forecasting AI progress is critical for AI safety work. The timeline to transformative AI shapes everything from research priorities to governance frameworks – if we expect transformative AI within 5 years versus 50 years, this dramatically changes which safety approaches are viable. For example, if we expect rapid progress, we might need to focus on safety measures that can be implemented quickly rather than long-term theoretical research. Additionally, understanding likely development trajectories helps us anticipate specific capabilities and prepare targeted safety measures before they emerge. This is especially critical given the potential for sudden capability jumps, especially in dangerous capabilities like malware generation or deception.

Methodology

How do we convert beliefs into probabilities and forecasts? We need some ways to actually convert beliefs like "I think AGI is likely this decade" into precise probability estimates. One way we can do this is by decomposition - breaking down complex beliefs into smaller, measurable components and analyzing relevant data. Rather than directly estimating the year in which transformative AI emerges, we can start by separately forecasting things like compute growth, algorithmic progress, and hardware limitations, and then combine these estimates (Zhang, 2024). This decomposition approach helps us ground predictions in observable trends rather than relying purely on intuitions. So, using this approach there are two main techniques we need to discuss - zeroth-order forecasting for establishing baselines, and first-order forecasting for understanding trajectories of change.

What are reference classes and why do they matter? When analyzing each component of our decomposed forecast, we need relevant historical examples to inform our predictions. This is where reference classes come in - they are categories of similar historical situations we can use to make predictions. For AI development, relevant reference classes might include things like previous technological revolutions (like the industrial or computer revolution), other optimization systems (like biological evolution or economies), or the impact of rapid scientific advances (like CRISPR or mRNA vaccines). The basic point is that they should be meaningfully analogous to what you're trying to predict, but they don't have to be from the same exact category.

What is zeroth-order forecasting? The simplest forecasting approach starts with recognizing that tomorrow often looks pretty close to today. Zeroth-order forecasting uses reference classes - looking at 3-5 similar historical examples and using their average as a baseline prediction. Rather than trying to identify trends or make complex projections, it assumes recent patterns will continue (Steinhardt, 2024).

What is first-order forecasting? While zeroth-order forecasting uses historical examples from various reference classes as direct predictors, first-order forecasting attempts to identify and project forward patterns in the direct historical data of AI development. In AI, we see some pretty consistent exponential growth patterns. The compute used in frontier models has grown by 4.2x annually since 2010, training datasets have expanded by approximately 2.9x per year, and hardware performance improves by roughly 1.35x every year through architectural advances (Epoch AI, 2023). First-order forecasting tries to identify these kinds of patterns and project them forward. This is the approach taken by most systematic AI forecasting work today, including Epoch AI's compute-centric framework and Ajeya Cotra's biological anchors. However, it's worth keeping in mind that even though these trends have been remarkably consistent, they can't continue indefinitely. Physical, thermodynamic, or economic constraints will eventually limit growth. The key question is: when do these limits become relevant? We will explore this in the next section on the compute centric framework.

How do we combine different forecasts? Multiple forecasting approaches often give us different predictions – zeroth-order might suggest one timeline while trend extrapolation indicates another. Just like we can average out over the opinions of many experts, we can integrate these predictions to get a hopefully more accurate picture. One approach is to model each forecast as a probability distribution and combine them using mixture models (Steinhardt, 2024).

What about situations with limited data or limited reference classes? While decomposition, reference classes and trend analysis form the backbone of AI forecasting, we sometimes face questions where direct data is limited or no clear reference classes exist. For instance, predicting the societal impact of advanced AI systems or forecasting novel capabilities that haven't been demonstrated before. In these cases, we often turn to expert judgment and superforecasters. An advantage of expert forecasting is the ability to integrate qualitative insights that might be missed by pure trend analysis. For example, experts might notice early warning signs of diminishing returns or identify emerging technical approaches that could accelerate progress. This balanced use of both data-driven methods and expert judgment is especially important for AI safety work. While we should ground our predictions in empirical trends whenever possible, we also need frameworks for reasoning about unprecedented developments and potential discontinuities in progress.

How far do empirical findings generalize? There's an ongoing debate about how much we can trust current trends to predict future AI development. Some researchers argue that empirical findings in AI generalize surprisingly far - that patterns we observe today will continue to hold even as systems become more capable (Steinhardt, 2022). However, our track record with forecasting suggests we should be cautious. When superforecasters predicted MATH dataset accuracy would improve from 44% to 57% by June 2022, actual performance reached 68% - a level they had rated extremely unlikely. Shortly after, GPT-4 achieved 86.4% accuracy. There are a couple of more examples of LLMs surprising most forecasters and experts on certain benchmarks (Cotra, 2023).

This pattern of underestimating progress suggests that while empirical trends provide valuable guidance, they may not capture all the dynamics of AI development. Prior to GPT-3, many experts believed tasks like complex reasoning would require specialized architectures. The emergence of these capabilities from scaling alone shows how systems can develop unexpected abilities simply through quantitative improvements. This has critical implications for both forecasting and governance - we need frameworks that can adapt to capabilities emerging faster or differently than current trends suggest.

How does this help us predict transformative AI? These forecasting fundamentals help us critically evaluate claims about AI timelines and takeoff scenarios. When we encounter predictions about discontinuous progress or smooth scaling, we can ask: What trends support this view? What reference classes are relevant? How have similar forecasts performed historically? This systematic approach helps us move beyond intuition to make more rigorous predictions about AI development trajectories.

Forecasting Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are like betting systems where people can buy and sell shares based on their predictions of future events. For example, if there’s a prediction market for a presidential election, you can buy shares for the candidate you think will win. If many people believe Candidate A will win, the price of shares for Candidate A goes up, indicating a higher probability of winning.

These markets are helpful because they gather the knowledge and opinions of many people, often leading to accurate predictions. For example, a company might use a prediction market to forecast whether a new product will succeed. Employees can buy shares if they believe the product will do well. If the majority think it will succeed, the share price goes up, giving the company a good indication of the product’s potential success.

By allowing participants to profit from accurate predictions, these markets encourage the sharing of valuable information and provide real-time updates on the likelihood of various outcomes. The argument is that either prediction markets are more accurate than experts, or experts should be able to make a lot of money from these markets and, in doing so, correct the markets. So the incentive for profit leads to the most accurate predictions. Examples of prediction markets include manifold, or metaculus.

When using prediction markets to estimate the reproducibility of scientific research it was found that they outperformed expert surveys (Dreber et al., 2015). So if a lot of experts participate, prediction markets might be one of our best probabilistic forecasting tools, better even than surveys or experts.

Trend Based Forecasting

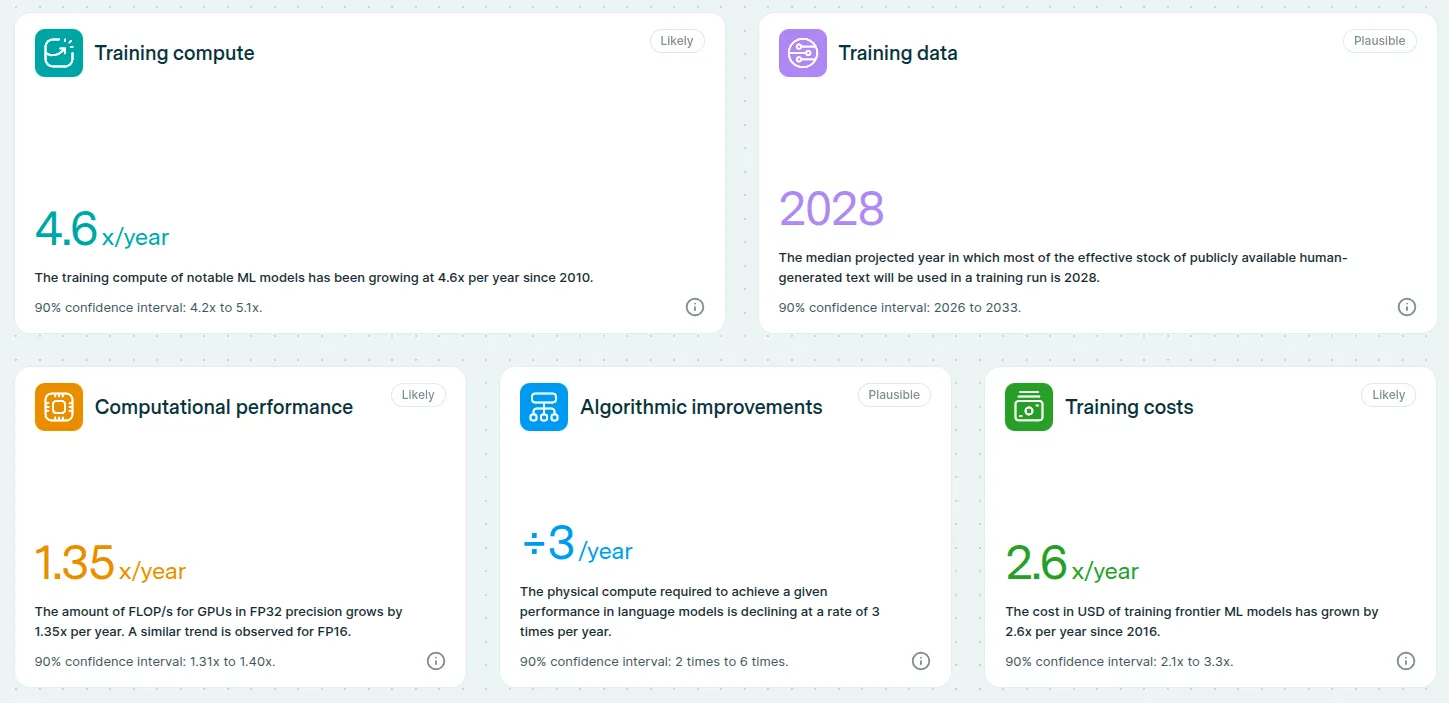

Generally, the three main components recognized as the main variables of advancement in deep learning are: computational power available, algorithmic improvements, and the availability of data. These three variables are also sometimes called the inputs to the AI production function, or the AI triad (Buchanan, 2022).

We can anticipate that models will continue to scale in the near future. Increased scale combined with the increasingly general-purpose nature of foundation models could potentially lead to a sustained growth in general-purpose AI capabilities.

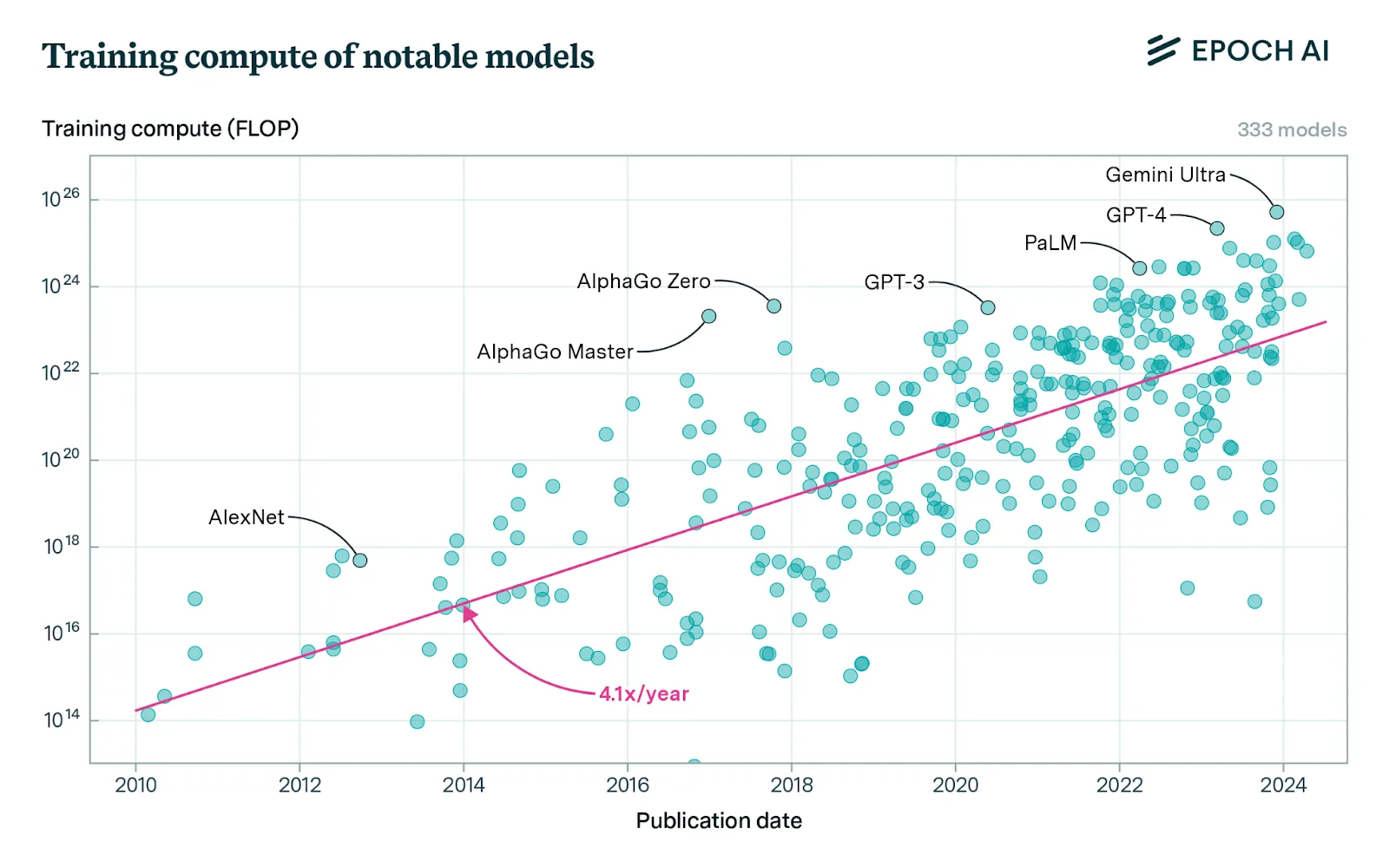

Compute

The first thing to look at is the trends in the overall amount of training compute required when we train our model. Training compute grew by 1.58 times/year up until the Deep Learning revolution around 2010, after which growth rates increased to 4.2 times/year. We also find a new trend of "large-scale" models that emerged in 2016, trained with 2-3 OOMs (Order Of Magnitude) more compute than other systems in the same period.

Hardware advancements are paralleling these trends in training compute and data. GPUs are seeing a yearly 1.35 times increase in floating-point operations per second (FLOP/s). However, memory constraints are emerging as potential bottlenecks, with DRAM capacity and bandwidth improving at a slower rate. Investment trends reflect these technological advancements

In 2010, before the deep learning revolution, DeepMind co-founder Shane Legg predicted human-level AI by 2028 using compute-based estimates (Legg, 2010). OpenAI co-founder Ilya Sutskever, whose AlexNet paper sparked the deep learning revolution, was also an early proponent of the idea that scaling up deep learning would be transformative.

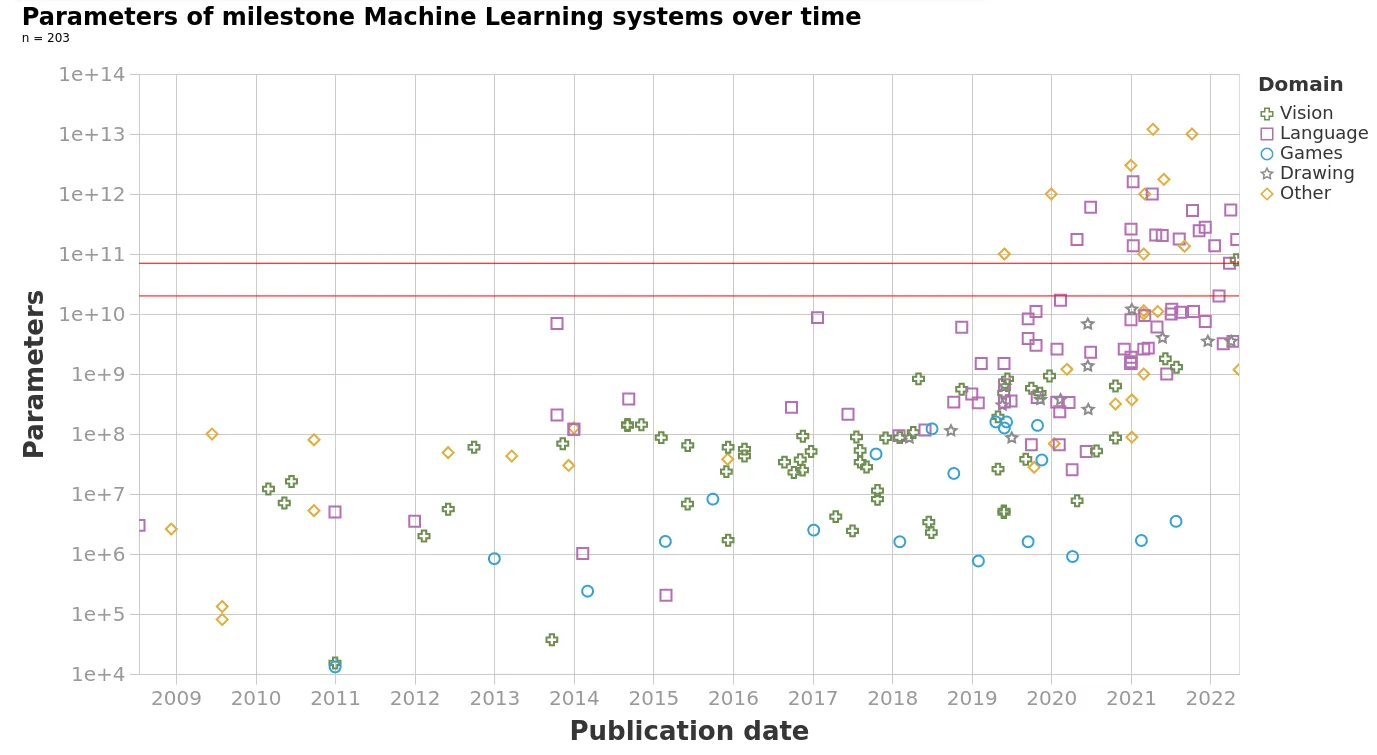

Parameters

In this section, let's look at the trends in model parameters. The following graph shows how even though parameter counts have always been increasing, in the new 2018+ era, we have really entered a different phase of growth. Overall, between the 1950s and 2018, models have grown at a rate of 0.1 orders of magnitude per year (OOM/year). This means that in the 68 years between 1950 and 2018 models grew by a total of 7 orders of magnitude. However, post-2018, in just the last 5 years models have increased by yet another 4 orders of magnitude (not accounting for however many parameters GPT-4 has because we don't know).

The following table and graph illustrate the trend change in machine learning models' parameter growth. Note the increase to half a trillion parameters with constant training data.

f

Data

We are using ever-increasing amounts of data to train our models. The paradigm of training foundation models to fine-tune later is accelerating this trend. If we want a generalist base model then we need to provide it with ‘general data’, which means: all the data we can get our hands on. You have probably heard that models like ChatGPT and PaLM are trained on data from the internet. The internet is the biggest repository of data that humans have. Additionally, as we observed from the Chinchilla papers scaling laws, it is possible that data to train our models is the actual bottleneck, and not compute or parameter count. So the natural question is how much data is left on the internet for us to keep training our models? and how much more data do we humans generate every year?

How much data do we generate?

The total amount of data generated every single day in 2019 was on the order of ~463EB (World Economic Forum, 2019). But in this post, we will assume that models are not training on ‘all the data generated’ (yet), rather they will continue to only train on open-source internet text and image data. The available stock of text and image data grew by 0.14 OOM/year between 1990 and 2018 but has since slowed to 0.03 OOM/year.

How much data is left?

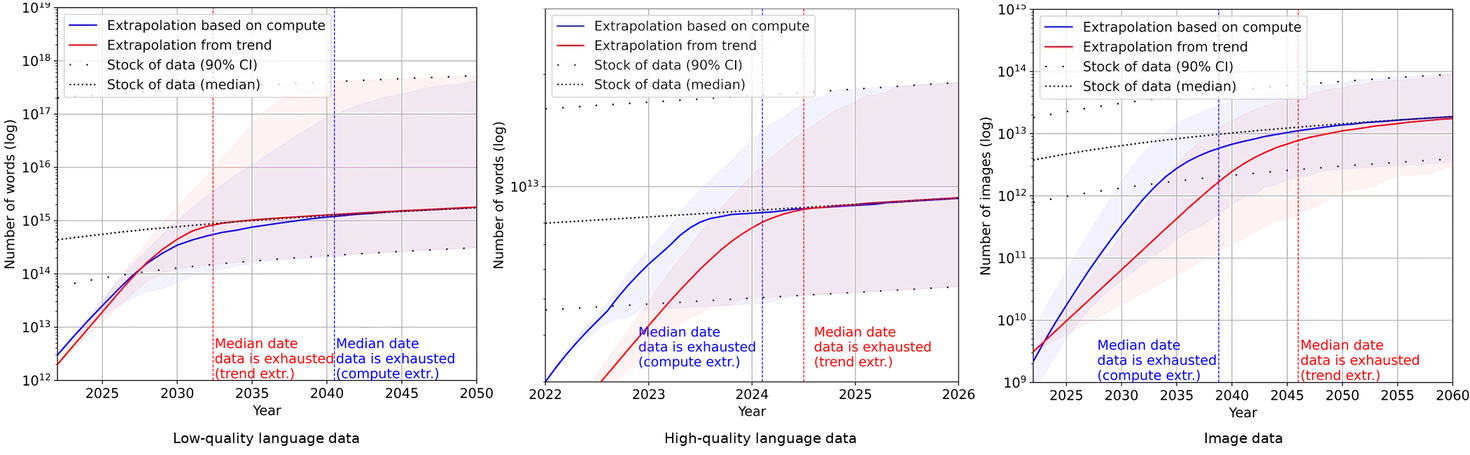

The median projection for when the training dataset of notable ML models exhausts the stock of professionally edited texts on the internet is 2024. The median projection for the year in which ML models use up all the text on the internet is 2040. Overall, projections by Epochai predict that we will have exhausted high-quality language data before 2026, low-quality language data somewhere between 2030 and 2050, and vision data between 2030 and 2060. This might be an indicator of slowing down ML progress after the next couple of decades. These conclusions from Epochai, like all the other conclusions in this entire leveraging computation section, rely on assumptions that current trends in ML data usage and production will continue and that there will be no major innovations in data efficiency, i.e. we are assuming that the amount of capabilities gained per training datapoint will not change from current standards.

Even if we run out of Data, many solutions are proposed, from using synthetic data, for example, filtering and preprocessing the data with GPT-3.5 to create a new cleaner dataset, an approach used in the paper "Textbooks are all you need" with models like Phi 1.5B that demonstrate excellent performance for their size through the use of high-quality filtered data, to the use of more efficient trainings, or being more efficient by training on more epochs.

Algorithms

Algorithmic advancements also play a role. For example, between 2012 and 2021, the computational power required to match the performance of AlexNet has been reduced by a factor of 40, which corresponds to a threefold yearly reduction in the compute required for achieving the same performance on image classification tasks like ImageNet. Improving the architecture also counts as algorithmic advancement. A particularly influential architecture is that of Transformers, central to many recent innovations, especially in chatbots and autoregressive learning. Their ability to be trained in parallel over every token of the context window fully exploits the power of modern GPUs, and this is thought to be one of the main reasons why they work so well compared to their predecessor, even if this point is controversial.

Does algorithmic architecture really matter?

This is a complicated question, but some evidence suggests that once an architecture is expressive and scalable enough, the architecture matters less than we might have thought:

In a paper titled ‘ConvNets Match Vision Transformers at Scale,' Google researchers found that Visual Transformers (ViT) can achieve the same results as CNNs (Convolutional neural network) simply by using more compute. (Smith et al., 2023) They took a special CNN architecture and trained it on a massive dataset of four billion images. The resulting model matched the accuracy of existing ViT systems that used similar training compute.

Variational AutoEncoders catch up if you make them very deep (Child, 2021; Vahdat & Kautz, 2021).

Progress in late 2023, such as the mamba architecture (Gu & Dao, 2023), appears to be an improvement on the transformer. It can be seen as an algorithmic advancement that reduces the amount of training computation needed to achieve the same performance.

The connections and normalizations in the transformer, which were thought to be important, can be taken out if the weights are set up correctly. This can also make the transformer design simpler (Note however that this architecture is slower to converge than the others). (He et al., 2023)

On the other side of the argument, certain attention architectures are significantly more scalable when dealing with long context windows, and no feasible amount of training could compensate for this in more basic transformer models. Architectures specifically designed to handle long sequences, like Sparse Transformers (Child et al., 2019) or Longformer (Beltagy et al., 2020), can outperform standard transformers by a considerable margin for this usage. In computer vision, architectures like CNNs are inherently structured to recognize spatial hierarchies in images, making them more efficient for these tasks than architectures not specialized in handling spatial data when the amount of data is limited, and the "prior" encoded in the architecture makes the model learn faster.

Costs

Understanding the dollar cost of ML training runs is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it reflects the real economic expense of developing machine learning systems, which is essential for forecasting the future of AI development and identifying which actors can afford to pursue large-scale AI projects. Secondly, by combining cost estimates with performance metrics, we can track the efficiency and capabilities of ML systems over time, offering insights into how these systems are improving and where inefficiencies may lie. Lastly, these insights help determine the sustainability of current spending trends and guide future investments in AI research and development, ensuring resources are allocated effectively to foster innovation while managing economic impact.

Moore’s Law, which predicts the doubling of transistor density and thus computational power approximately every two years, has historically led to decreased costs of compute power. However, the report finds that spending on ML training has grown much faster than the cost reductions suggested by Moore’s Law. This means that while hardware has become cheaper, the overall expense of training ML systems has escalated due to increasing demand for computational resources. This divergence emphasizes the rapid pace of advancements in ML and the significant investments required to keep up with the escalating computational demands.

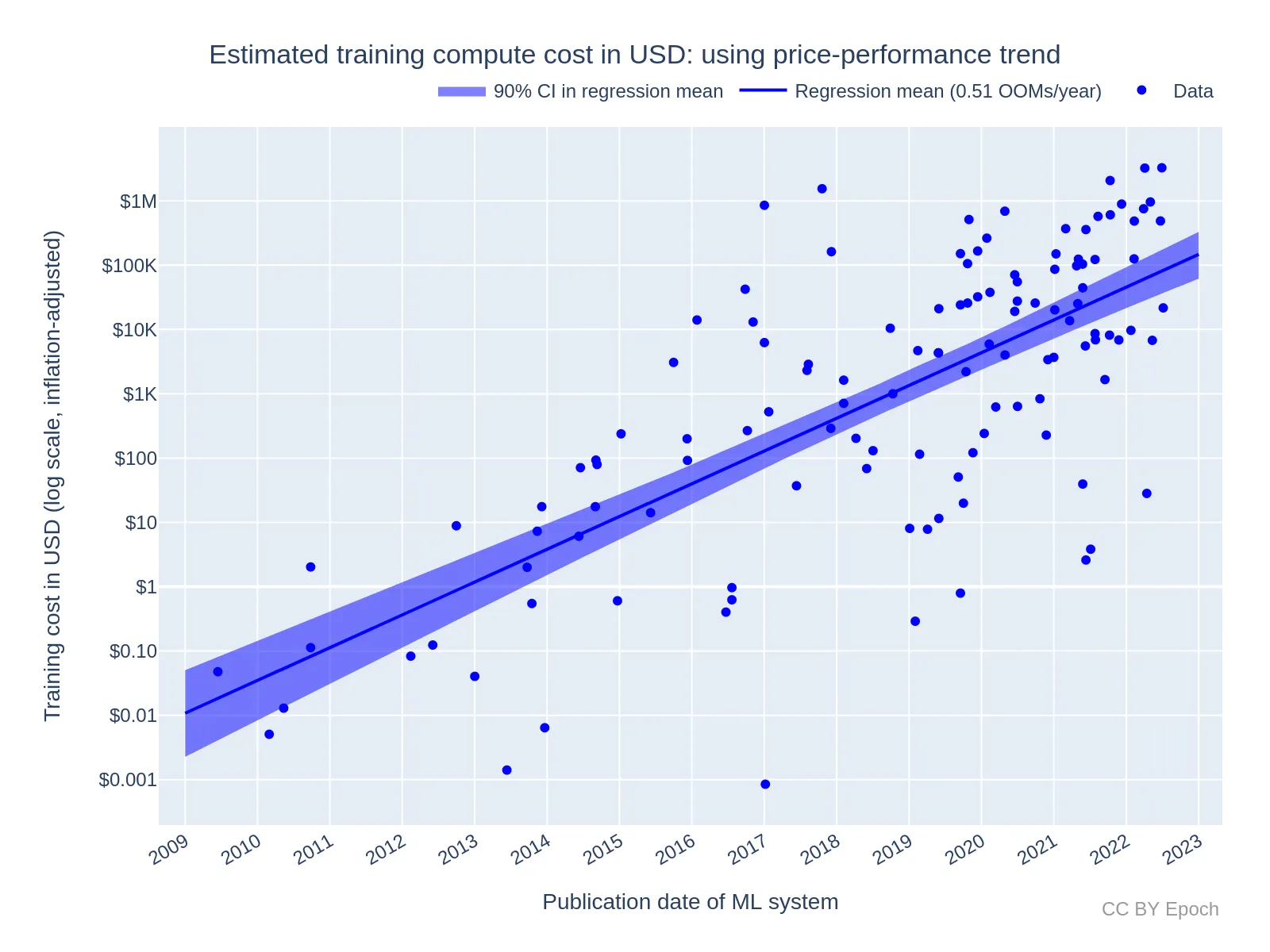

To measure the cost of ML training runs, the report employs two primary methods. The first method uses historical trends in the price-performance of GPUs to estimate costs. This approach leverages general trends in hardware advancements and cost reductions over time. The second method bases estimates on the specific hardware used to train the ML systems, such as NVIDIA GPUs, providing a more detailed and accurate picture of the costs associated with particular technologies. Both methods involve calculating the hardware cost—the portion of the up-front hardware cost used for training—and the energy cost, which accounts for the electricity required to power the hardware during training. These calculations provide a comprehensive view of the economic burden of training ML models.

Measuring the cost of development extends beyond the final training run of an ML system to encompass a range of factors. This includes research and development costs, which cover the expenditures on preliminary experiments and model refinements that lead up to the final product. It also involves personnel costs, including salaries and benefits for researchers, engineers, and support staff. Infrastructure costs, such as investments in data centers, cooling systems, and networking equipment, are also significant. Additionally, software and tools, including licenses and cloud services, contribute to the overall cost. Energy costs throughout the development lifecycle, not just during the final training run, and opportunity costs—potential revenue lost from not pursuing other projects—are also crucial components. Understanding these broader costs provides a more comprehensive view of the economic impact of developing advanced ML systems, informing strategic decisions about resource allocation.

The findings suggest that the cost of ML training runs will continue to grow, but the rate of growth might slow down in the future. The report estimates that the cost of ML training has grown by approximately 2.8 times per year for all systems. For large-scale systems, the growth rate is slower, at around 1.6 times per year. This substantial year-on-year increase in training costs highlights the need for significant efficiency improvements in both hardware and training methodologies to manage future expenses effectively.

The report forecasts that if current trends continue, the cost for the most expensive training runs could exceed significant economic thresholds, such as 1% of the US GDP, within the next few decades. This implies that without efficiency improvements, the economic burden of developing state-of-the-art ML systems will increase substantially. Consequently, understanding and managing these costs is essential for ensuring the sustainable growth of AI capabilities and maintaining a balanced approach to AI investment and development.