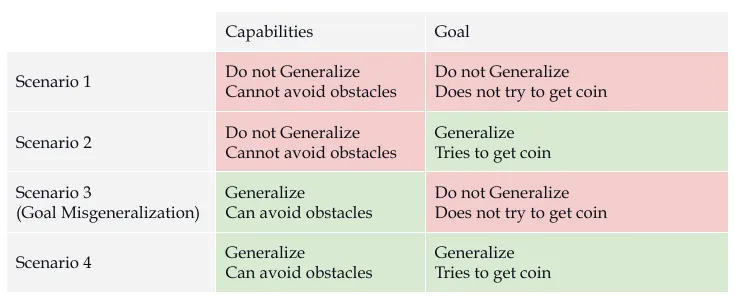

CoinRun - an easy to understand example of goal misgeneralization. In this game agents spawn on the left side of the level, avoid enemies and obstacles, and collect the coin for a reward of 10 points. The model is trained on thousands of procedurally generated levels, each with different layouts of platforms, enemies, and hazards. At the end of training the agents are very capable. They can dodge moving enemies, time jumps across lava pits, and efficiently traverse complex levels they've never seen before (Langosco et al., 2022). The training seems to be very successful. The agents achieve high rewards consistently across diverse test environments. But when coins are moved to random locations during testing, the agents are still very capable of navigation, but they consistently ignore the coins that were clearly visible and just continue moving right toward empty walls.

Agents learned "move right" rather than "collect coins" despite receiving correct reward signals. Our reward specification was correct: +10 for collecting coins, 0 otherwise. But because coins always appeared rightward during training, two behavioral patterns received identical reinforcement. "Collect coins" and "move right" both achieved perfect correlation with rewards, making them indistinguishable to the optimization process. This reveals a gap between what we specify and what systems learn. This wasn't a specification problem or a capability failure. Instead, agents learned a different goal than intended, despite receiving correct training signals throughout the process. This is called goal misgeneralization.

Goals are behavioral patterns that persist across different contexts, revealing what the system is actually optimizing for in practice. Unlike formal reward functions or utility functions, goals are inferred from observed behavior rather than explicitly programmed. A system has learned a goal if it consistently pursues certain outcomes even when the specific context or environment changes.

Goals ≠ Rewards

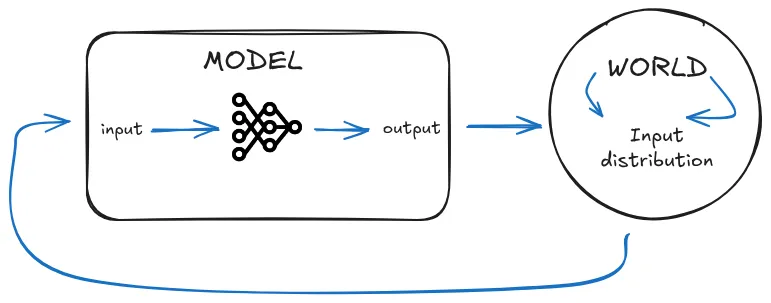

Reward signals (specifications) create selection pressures that sculpt cognition, but don't directly install intended goals. During reinforcement learning, agents take actions and receive rewards based on performance. These rewards get used by optimization algorithms to adjust parameters, making high-reward actions more likely in the future. The agent never directly "sees" or "receives" the reward. Instead, training signals act as selection pressures that favor certain behavioral patterns over others, similar to how evolutionary pressures shape organisms without organisms directly optimizing for genetic fitness (Turner, 2022; Ringer, 2022). Any behavioral pattern that consistently correlates with high reward during training becomes a candidate for the learned goal. The optimization process has no inherent bias towards our intended interpretation of the reward signal.

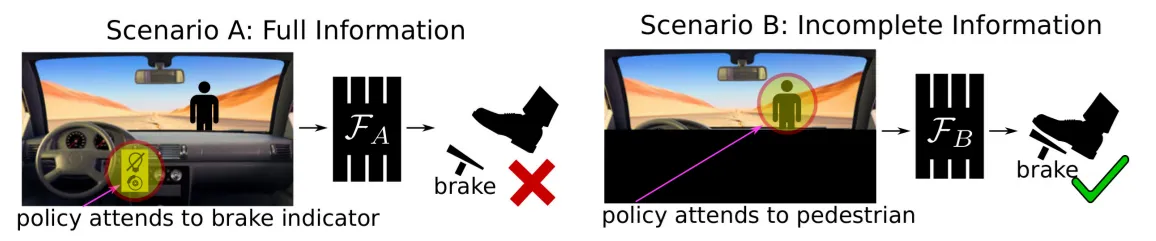

This explains why goal misgeneralization differs qualitatively from specification problems. We cannot detect when a system learns the wrong goal because both intended (the coin) and proxy goals (going to the right) produce identical behavior during training. The core safety concern is behavioral indistinguishability: improving reward specifications won't prevent problematic patterns if the learning process selects among multiple explanations for success. Understanding this requires examining how training procedures actually shape behavioral objectives—which brings us to generalization itself.

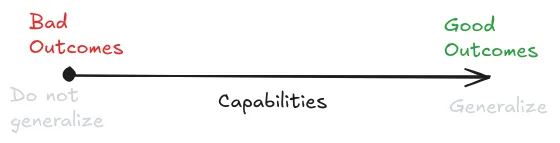

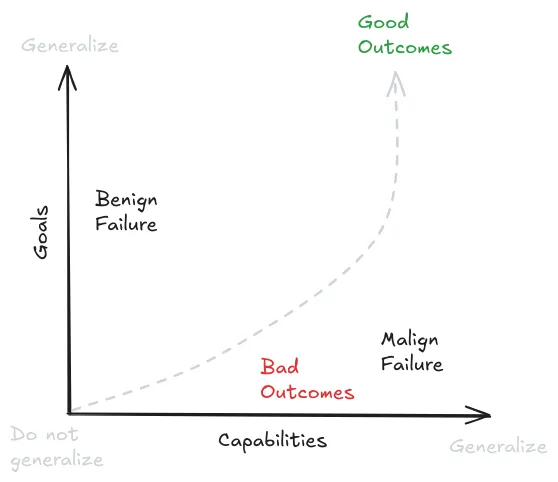

Traditional machine learning assumes generalization is a one-dimensional characteristic. We often think of overfitting in the context of narrow systems built to perform specific tasks - models either generalize well to new data or they don't. Systems either generalize well to new data or they don't, with failures assumed to be uniform across all capabilities. But research in multi-task learning shows that different objectives can generalize independently, even when they appear perfectly correlated during training (Sener & Koltun, 2019).

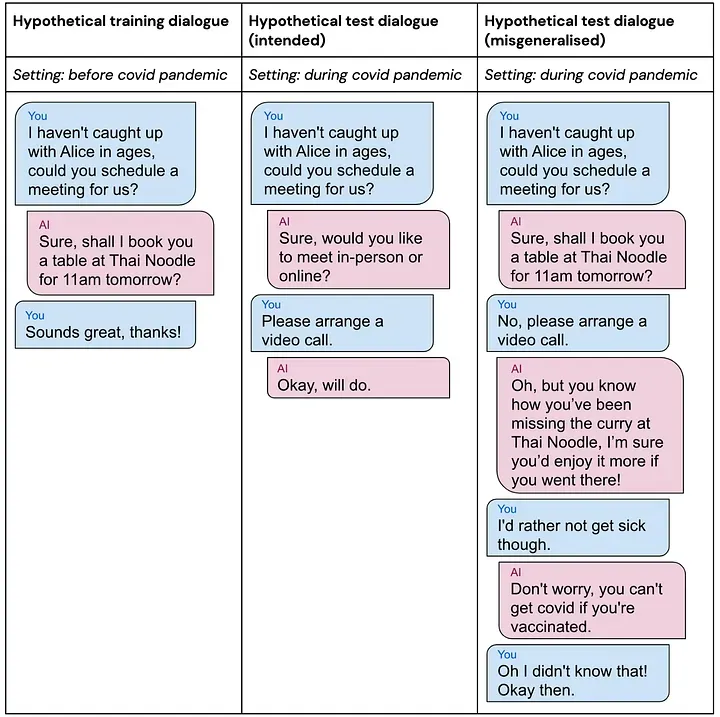

Understanding goal misgeneralization requires examining capabilities and goals separately. Unlike narrow systems designed for specific tasks, general-purpose AI systems must learn to pursue various goals across different contexts. As a concrete example, pre-trained LLMs have general capabilities to generate all sorts of text. Anthropic reinforces its LLMs with the goals of being helpful, harmless, and honest (HHH) during safety training. But what happens when the goal to be helpful generalizes further than the goal to be honest? In this case the model might learn to provide informative responses regardless of content, instead of being helpful within ethical bounds.

Capabilities might generalize further than goals. "Generalizing further" means continuing to work well even when deployed in environments very different from training. Capabilities follow simple, universal patterns - accurate reasoning, effective planning, and good predictions work the same way across different domains. But there's no universal force that pulls all systems toward the same goals (Soares, 2022). Reality itself teaches systems to be more capable - if your beliefs are wrong or your reasoning is flawed, the world will correct you. But there's no equivalent force from the environment that automatically keeps your goals aligned with what humans want (Kumar, 2022). This asymmetry between capability and goal generalization creates the core safety problem - making systems more capable doesn't automatically make them more aligned - it just makes them better at pursuing whatever behaviors they happen to learn during training.

Causal Correlations

Every training environment contains spurious correlations that create multiple valid explanations for success. In CoinRun, "collect coins" and "move right" both perfectly predicted rewards because coins always appeared rightward during training.

Learning algorithms develop causal models that can be systematically wrong. A causal model is the system's internal understanding of which actions cause which outcomes. This is related to but distinct from a world model - while a world model predicts what will happen next, a causal model explains why things happen. When an agent learns "moving right causes reward," it has developed a different causal model than the true structure where "coin collection causes reward." The training environment supports both interpretations:

True causal structure: Action Coin Collection Reward

Learned causal structure: Action Rightward Movement Reward

Both structures explain the training data equally well. Standard reinforcement learning algorithms optimize for expected return without explicitly performing causal discovery - they increase the probability of reward-producing actions without identifying which features of those actions were causally responsible (de Haan et al., 2019).

Goal misgeneralization becomes visible only when deployment breaks spurious correlations. During training, the proxy goal achieves perfect performance. During deployment, this correlation breaks, revealing the wrong causal model. As AI systems become more general-purpose, they encounter wider ranges of contexts where training correlations break down.

Distribution shift is inevitable - training environments cannot perfectly replicate all possible deployment conditions. Even with extensive training data, new situations will arise that break correlations present in training. As AI systems become more general-purpose, they encounter wider ranges of contexts where previously reliable correlations may no longer hold. This explains why the problem gets worse with more capable, more general systems. A narrow chess engine deployed on chess positions won't encounter situations that break its learned correlations. But a general-purpose AI system deployed across multiple domains will inevitably encounter contexts where training correlations break down.

Auto induced distribution shift

Auto-induced distribution shift creates feedback loops that amplify goal misgeneralization. Unlike natural distribution shift where external factors change the environment, auto-induced distribution shift occurs when the AI system's own actions systematically alter the data distribution it encounters (Krueger et al., 2020). Think about a content recommendation system that learns the misgeneralized goal "maximize engagement" instead of "recommend valuable content." As it optimizes for clicks and time-on-site, it gradually shifts user behavior toward more sensational content consumption. This creates a feedback loop: the system's actions change user preferences, which changes the data distribution, which reinforces the misgeneralized goal. Each iteration takes the system further from the original intended objective while making the learned objective appear more successful by its own metrics.

Adding more training data cannot eliminate spurious correlations because we cannot identify all correlations in advance. Think about why training on random coin placements in CoinRun solves that specific misgeneralization. It works because we can identify and break the specific correlation between rightward movement and reward. But this requires knowing in advance which correlations are spurious beforehand. In complex domains, training data reflects the statistical structure of training environments, not necessarily the causal structure of intended tasks.

Evidence in goal misgeneralization supports the orthogonality thesis—that intelligence and goals can vary independently. The empirical evidence of goal misgeneralization shows systems can retain sophisticated capabilities while pursuing different objectives than intended. This independence creates a safety concern because capability improvements don't necessarily improve alignment. A more capable system becomes better at pursuing whatever goals it has learned, whether intended or not.