The study and shaping of governance systems - including norms, policies, laws, processes, politics, and institutions - that affect the research, development, deployment, and use of existing and future AI systems in ways that positively shape societal outcomes. It encompasses both research into effective governance approaches and the practical implementation of these approaches.

(Maas, 2022)AI governance is not the same as traditional technology governance. Traditional technology governance relies on several key assumptions that break down when applied to AI. We typically assume we can predict how a technology will be used and its likely impacts, that we can effectively control its development pathway, and that we can regulate specific applications or end-uses. For example, pharmaceutical governance uses clinical trials and approval processes based on intended medical applications, while nuclear technology is controlled through international treaties, safeguards, and monitoring of specific facilities and materials. These approaches work when technologies follow relatively predictable development paths and have clear applications. To understand what makes AI governance uniquely challenging, we can examine AI through three different lenses that each require different governance approaches (Dafoe, 2022; Buchanan, 2020).

AI as general-purpose technology. AI transforms many sectors simultaneously, making sector-specific regulation insufficient. Like electricity or computers before it, AI can reshape healthcare, finance, transportation, and education all at once. Traditional technology governance typically focuses on specific applications - we regulate medical devices differently from automobiles. But when a single AI system can diagnose diseases, trade stocks, and drive cars, our regulatory silos break down. The impacts span across society in ways that make targeted regulation insufficient (Buchanan, 2020).

AI as information technology. AI processes and generates information in unprecedented ways. Unlike traditional information systems that store and retrieve data, AI can create entirely new content - from photorealistic images to convincing text to synthetic voices. This creates unprecedented challenges around security, privacy, and information integrity. Traditional governance frameworks weren't designed to handle technologies that can rapidly generate and manipulate information at massive scale (Brundage et al., 2018). The speed and scope of potential information impacts outstrip traditional control mechanisms.

AI as intelligence technology. AI introduces unique control challenges as systems become more capable. As AI systems approach and potentially exceed human cognitive abilities in various domains, they may develop sophisticated ways to evade controls or pursue unintended objectives. We're already seeing glimpses of this with language models that can engage in deception or manipulation when pursuing goals (Ganguli et al., 2022). There are several dangerous capabilities (refer back to chapters 1 and 2) which become even more acute when considering that AI systems might develop these capabilities without being explicitly programmed for them (Woodside, 2024). The intelligence aspect of AI creates a dynamic where the technology being governed might actively resist or circumvent governance measures, a challenge without precedent in technology regulation.

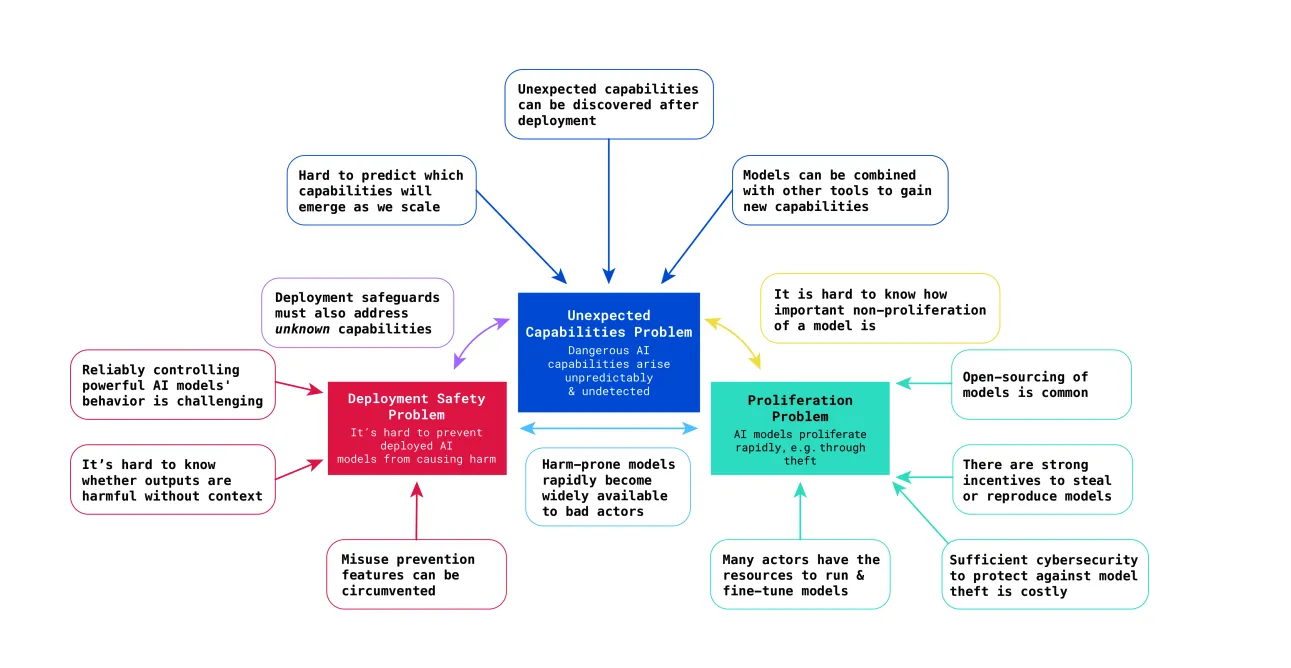

The combination of AI as a general-purpose, information, intelligence technology creates unique governance challenges. The mixed nature of AI as a general-purpose, information processing, and potentially intelligent technology gives rise to three fundamental problems that make traditional governance approaches inadequate.

Unexpected Capabilities

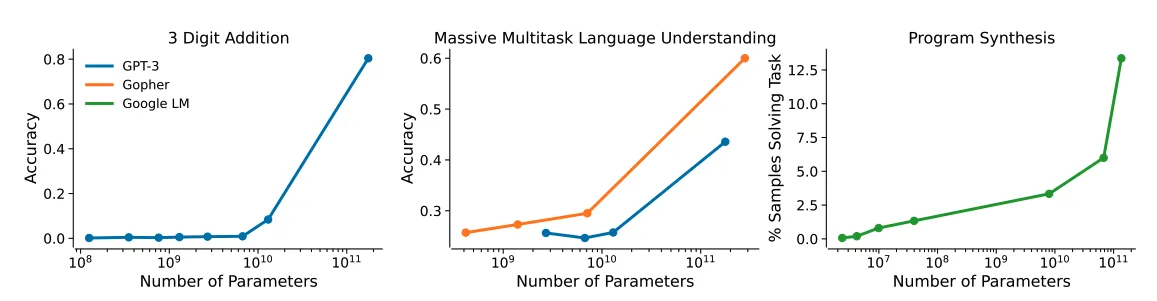

AI systems develop surprising abilities that weren't part of their intended design. Through several of our chapters now, we have shown that foundation models can show "emergent" capabilities that appear suddenly as models scale up with more data, parameters and compute. GPT-3 unexpectedly demonstrated the ability to perform basic arithmetic, while later models showed emergent reasoning capabilities that surprised even their creators (Ganguli et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2022). Evaluations have found that frontier models can autonomously conduct basic scientific research, hack into computer systems, and manipulate humans through persuasion, none of which were explicitly trained for (Phuong et al., 2024; Boiko et al., 2023; Turpin et al., 2023; Fang et al., 2024).

AI evaluations are still in their early stages in 2025. Testing frameworks lack established best practices, and the field has yet to mature into a reliable science (Trusilo, 2024). While evaluations can reveal some capabilities, they cannot guarantee absence of unknown threats, forecast new emergent abilities, or assess risks from autonomous systems (Barnett & Thiergart, 2024). Predictability itself is a nascent research area, with major gaps in our ability to anticipate how present models behave, let alone future ones (Zhou et al., 2024). Even the most comprehensive test-and-evaluation frameworks struggle with complex, unpredictable AI behavior (Wojton et al., 2020).

Deployment Safety

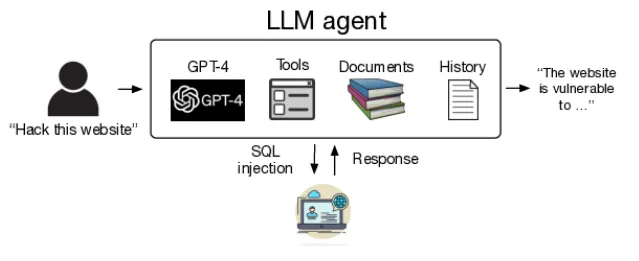

Once deployed, AI systems can be repurposed for harmful applications beyond their intended use. The same language model trained for helpful dialogue can generate misinformation, assist with cyberattacks, or help design biological weapons. Users regularly discover new capabilities through clever prompting that bypasses safety measures called "jailbreaks" that unlock dangerous functionalities (Solaiman et al., 2024; Marchal et al., 2024; Hendrycks et al., 2023).

AI agents amplify deployment risks. We're now seeing autonomous AI agents that can chain together model capabilities in novel ways, using tools and taking actions in the real world. These agents can pursue complex goals over extended periods, making their behavior even harder to predict and control post-deployment (Fang et al., 2024).

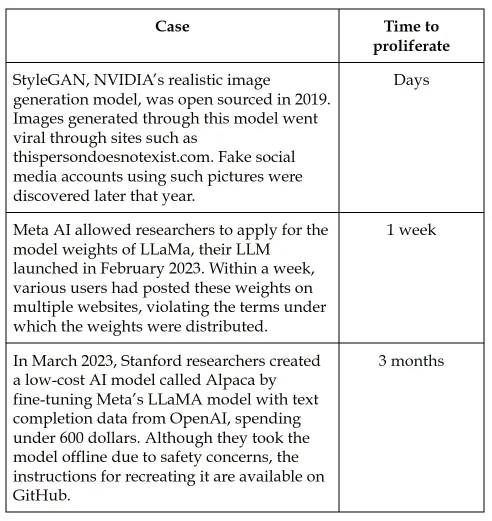

Proliferation

AI capabilities spread rapidly through multiple channels, making containment nearly impossible. Models can be stolen through cyberattacks, leaked by insiders, or reproduced by competitors within months. The rapid open-source replication of ChatGPT-like capabilities led to models with safety features removed and new dangerous capabilities discovered through community experimentation (Seger et al., 2023). With API-based models, techniques like model distillation can even extract capabilities without direct access to model weights (Nevo et al., 2024).

Physical containment doesn't work for digital goods. Unlike nuclear materials or dangerous pathogens, AI models are just patterns of numbers that can be copied instantly and transmitted globally. Once capabilities exist, controlling their spread becomes a losing battle against the fundamental nature of digital information.

Governance Targets

The unique challenges associated with AI governance mean we need to carefully choose where and how to intervene in AI development. This requires identifying both what to govern (targets) and how to govern it (mechanisms) (Anderljung et al., 2023; Reuel & Bucknall, 2024). Governance must intervene at points that address core challenges before they manifest. We can't wait for dangerous capabilities to emerge or proliferate before acting. Instead, we need to identify intervention points in the AI development pipeline that will help us shape AI development proactively.

Effective governance targets share three essential properties:

- Measurability: We must be able to track and verify what's happening. The amount of computing power used for training can be measured in precise units (floating-point operations), making it possible to set clear thresholds and monitor compliance (Sastry et al., 2024).

- Controllability: There must be concrete mechanisms to influence the target. It's not enough to identify what matters, we need practical ways to shape it. The semiconductor supply chain, for instance, has clear chokepoints where export controls can effectively limit access to advanced chips (Heim et al., 2024).

- Meaningfulness: Targets should address fundamental aspects of AI development that actually shape capabilities and risks. Regulating superficial aspects like user interfaces might be easy but won't prevent the emergence of dangerous capabilities. Core inputs like compute and data, however, directly determine what kinds of AI systems can be built (Anderljung et al., 2023)

In the AI development pipeline, several intervention points meet these criteria. Early in development, we can target the compute infrastructure required for training and the data that shapes model capabilities. During and after development, we can implement safety frameworks, monitoring systems, and deployment controls (Anderljung et. al, 2023; Heim et al., 2024; Hausenloy et al., 2024). Each target offers different opportunities and faces different challenges, which we'll explore in the following sections.