AI Safety Standards

What approaches exist for developing AI safety standards at the national level? Various approaches to developing safety standards exist within national contexts, from government-led standardization bodies to public-private collaborative processes. National standards bodies play a critical role in developing and implementing AI safety standards that align with each country's policy priorities and technological capabilities (Cihon, 2019). The EU AI Act demonstrates this through its requirement for a Code of Practice that specifies high-level obligations for General-Purpose AI models. In the United States, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has developed an AI Risk Management Framework that serves as a voluntary standard within American jurisdiction. In 2021, the Standardization Administration of China (SAC) released a roadmap for AI standards development that includes over 100 technical and ethical specifications from algorithmic transparency to biometric recognition safety. Coordinated by government agencies such as the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the China Electronics Standardization Institute (CESI). Unlike in the US or EU, where standards are often multistakeholder-developed or market-driven, China’s process is highly centralized and closely linked to its broader geopolitical ambitions (Ding, 2018).

How do national standards bodies develop effective AI safety standards? National standards have experience in governing various socio-technical issues within their countries. For example, national cybersecurity standards have spread across industries, environmental sustainability standards have prompted significant corporate investments, and safety standards have been implemented across sectors from automotive to energy. Expertise from other high-stakes industries can be leveraged to develop effective AI safety standards tailored to a country's specific needs and regulatory environment (Cihon, 2019). National standards can be used to spread a culture of safety and responsibility in AI research and development in four ways:

- The criteria within standards establish rules and expectations for safety practices within the country's AI ecosystem.

- Standards embed individual researchers and organizations within a larger network of domestic accountability.

- Regular implementation of standards helps researchers internalize safety routines as part of standard practice.

- When standards are embedded in products and software packages, they reinforce safety considerations regardless of which domestic organizations use the system.

These mechanisms help create what some researchers have called a "safety mindset" among AI practitioners within the national AI ecosystem. National standards serve as effective tools for fostering a culture of responsibility and safety in AI development, which is essential for long-term societal benefit (Cihon, 2019).

Regulatory Visibility

Regulatory visibility requires active, independent scrutiny of AI systems before, during, and after deployment. As frontier AI systems become increasingly integrated into society, external scrutiny (involving outside actors in the evaluation of AI systems) offers a powerful tool for enhancing safety and accountability. Effective external scrutiny should adhere to the ASPIRE framework, which proposes six criteria for effective external evaluation (Anderljung et al., 2023):

- Access: External scrutineers need appropriate access to AI systems and relevant information.

- Searching attitude: Scrutineers should actively seek out potential issues and vulnerabilities.

- Proportionality to the risks: The level of scrutiny should match the potential risks posed by the system.

- Independence: Scrutineers should be free from undue influence from AI developers.

- Resources: Adequate resources must support thorough scrutiny.

- Expertise: Scrutineers must possess the necessary technical and domain-specific expertise.

Some countries are exploring model registries, which are centralized databases that include architectural details, training procedures, performance metrics, and societal impact assessments. These registries support structured oversight and can act as early-warning systems for emerging capabilities, helping regulators detect dangerous trends before they materialize as harms (McKernon et al., 2024). Different jurisdictions take different approaches, but model documentation typically encompasses:

- Basic documentation (model identification, intended use cases)

- Technical specification (architecture, parameters, computational requirements)

- Performance documentation (benchmark results, capability evaluations)

- Impact assessment (societal effects, safety implications, ethical considerations)

- Deployment documentation (implementation strategies, monitoring plans)

Another method of regulatory visibility for AI is the Know Your Customer (KYC) system. KYC systems are already an established part of financial regulation, used to detect and prevent money laundering and terrorist financing. They have proven effective in their ability to identify high-risk actors before a transaction takes place. The same principle can be applied to compute access. As discussed in the compute governance section, frontier models require massive computational resources, often concentrated in a small number of hyperscale providers who serve as natural regulatory chokepoints. A KYC system for AI would enable governments to detect the development of potentially hazardous systems early, prevent covert model training, and implement export controls or licensing requirements with greater precision. Since this approach targets capability thresholds rather than use cases, it could serve as a preventative tool for risk management rather than a reactive one to deployment failures (Egan & Heim, 2023). However, implementing a KYC regime for compute involves several open questions. Providers would need clear legal mandates, technical criteria for client verification, and processes for escalating high-risk cases to authorities. Jurisdictional fragmentation is a challenge. Many developers rely on globally distributed compute services, and without international cooperation, KYC regimes risk being undercut by regulatory arbitrage. To be effective, a compute-based KYC system would need to align with other transparency mechanisms, such as model registries and incident reporting systems (Egan & Heim, 2023).

How can national policies support responsible information-sharing? Responsible reporting of information is important for both self-regulation and government oversight. As we discussed in the corporate governance section, companies developing and deploying frontier AI systems have primary access to information about their systems' capabilities and potential risks, and sharing this information responsibly can significantly improve the state's ability to manage AI risks (Kolt et al., 2024). National policies must address the tension between transparency and proprietary control. One approach is tiered disclosure, in which technical documentation is provided to regulators under confidentiality agreements while public communication remains high-level and risk-focused. Another approach is through anonymized or aggregated sharing of data, which enables statistical insight without revealing sensitive implementation details.

Although incident reporting systems from other industries, such as the confidential and non-punitive Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) in the United States, offer useful precedents, no equivalent system yet exists for AI. In aviation, it is clear what constitutes an incident or near-miss, but with AI, the lines can be blurry. Adapting this model would require clear definitions of what constitutes an “incident,” with structured categories ranging from model misbehavior to societal harms. Current national efforts on this are fragmented. In the EU, the AI Act mandates reporting of “serious incidents” by high-risk and general-purpose AI developers. In China, the Cyberspace Administration is building a centralized infrastructure for real-time reporting of critical failures under cybersecurity law. In the United States, incident reporting remains sector-specific, with preliminary efforts underway in health and national security (Farrell, 2024; Cheng, 2024; OECD, 2025).

Ensuring Compliance

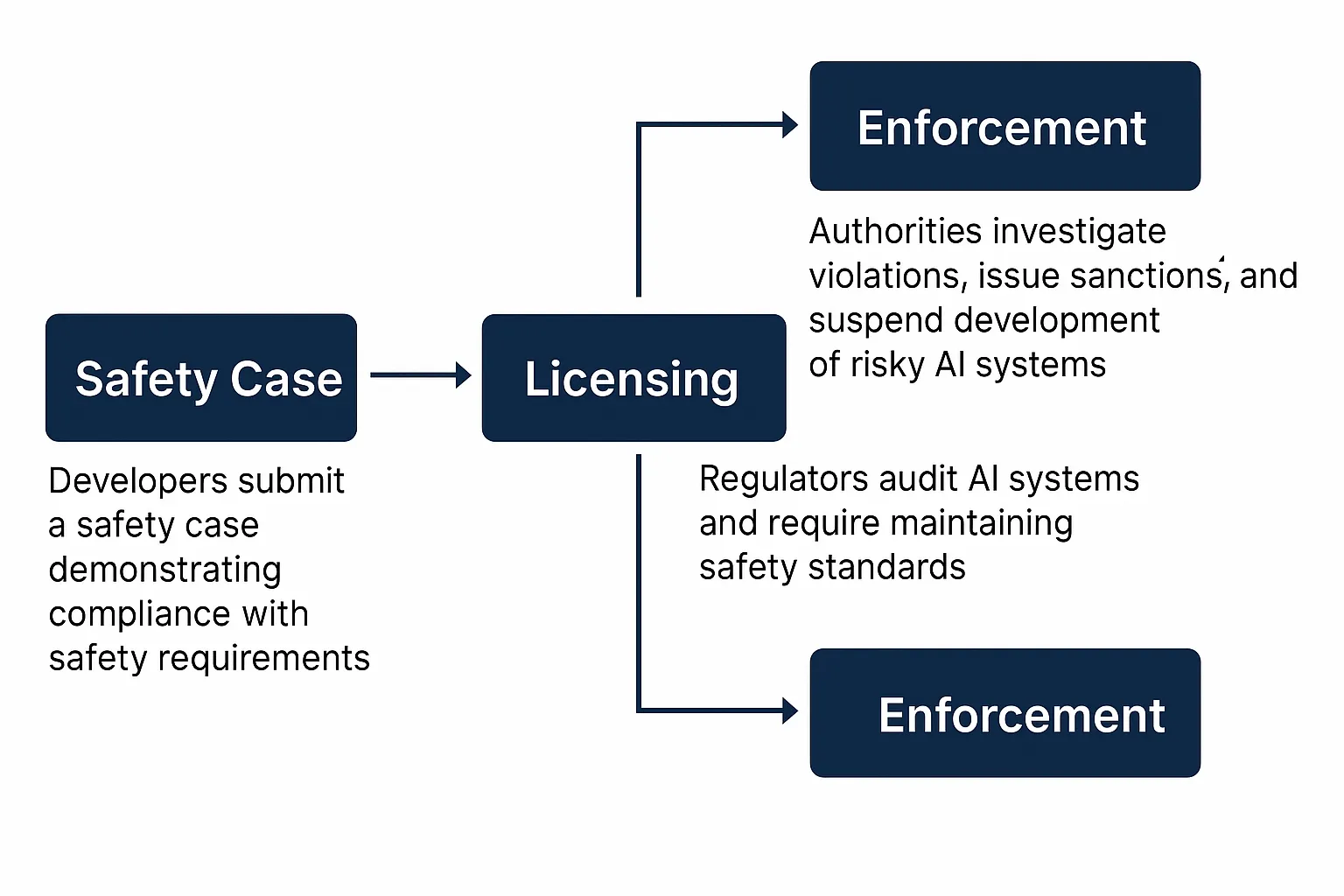

What regulatory tools can ensure compliance with AI safety standards? For high-risk AI systems, oversight mechanisms must go beyond voluntary standards or one-time evaluations. Many researchers have proposed licensing regimes that would mirror regulatory practices in sectors such as pharmaceuticals or nuclear energy. In these domains, operators must obtain and maintain licenses by demonstrating continuous compliance with strict safety and documentation requirements. Applied to frontier AI, this approach would involve formal approval processes before model deployment, periodic audits, and the ability for authorities to revoke licenses in cases of non-compliance (Buhl et al., 2024). A credible licensing framework would require developers to submit a structured safety case, which is a formal argument supported by evidence showing that a system meets safety thresholds for deployment. This could include threat modeling, red-teaming results, interpretability evaluations, and post-deployment monitoring plans. Safety cases provide a mechanism for both ex ante approval and for tracking whether safety claims continue to hold as systems evolve in deployment. Embedding these requirements into the licensing process can help governments establish a continuous cycle of review, feedback, and technical verification (Buhl et al., 2024).

How would enforcement work in practice? Licensing frameworks must be supported by agencies with the power to investigate violations, impose sanctions, and suspend development. National enforcement practices vary between horizontal governance (applying general rules across sectors) and vertical regimes (targeting specific domains like healthcare or finance) (Cheng & McKernon, 2024). For example, the European Union’s AI Act establishes enforcement authority through horizontal governance framework with the European AI Office, which can investigate, issue fines up to 3% of global annual turnover, and mandate corrective action, combined with mandatory incident reporting, systemic risk mitigation requirements, and a supporting Codes of Practice for GPAI models (Cheng & McKernon, 2024). In contrast, China’s Cyberspace Administration (CAC) exercises centralized enforcement powers under a vertical regulatory framework. While its approach prioritizes rapid intervention and censorship compliance, the CAC lacks transparent procedural checks and often relies on vague criteria for enforcement. In the United States, enforcement is fragmented. While export controls are strictly applied through agencies like the Department of Commerce, broader AI safety compliance has been delegated to individual agencies, with no national licensing authority. As a result, enforcement actions are often reactive and domain-specific, and rely on discretionary executive powers (Cheng & McKernon, 2024). Striking the right balance between these approaches will depend on institutional capacity, developer incentives, and the pace of AI advancement. In some cases, using existing sectoral authorities may suffice. In others, new institutions will be required to handle general-purpose capabilities that fall outside traditional regulatory categories (Dafoe, 2023).

Limitations and Trade-Offs

Every governance approach faces fundamental constraints that no amount of institutional design can fully overcome. Understanding these limitations helps set realistic expectations and identifies where innovation is most needed (Dafoe, 2023).

Some risks resist technical solutions. Despite advances in interpretability and evaluation, we still cannot fully understand or predict AI behavior. Black box models make verification difficult. Emergent capabilities appear unexpectedly. The gap between our governance ambitions and technical capabilities are substantial (Mukobi, 2024). Current safety techniques like RLHF and constitutional AI show promise for today's models but may fail catastrophically with more capable systems. We're building governance frameworks around safety approaches that might become obsolete. This fundamental uncertainty requires adaptive frameworks that can evolve with understanding (Ren et al., 2024).

Measurement challenges undermine accountability. We lack robust metrics for many safety-relevant properties. How do you measure a model's tendency toward deception? Its potential for autonomous improvement? Its resistance to misuse? Without reliable measurements, compliance becomes a matter of interpretation rather than verification (Narayan & Kapoor, 2024). The EU AI Act, for example, requires "systemic risk" assessments, but provides limited guidance on how to measure such risks quantitatively (Cheng, 2024).

Expertise shortages create critical bottlenecks. The number of individuals who deeply understand both advanced AI systems and governance remains extremely limited, and this gap exists at every level from company safety teams and regulators to international bodies. A lack of interdisciplinary talent undermines efforts to anticipate and manage emerging risks (Brundage et al., 2018). Institutional capacity for technical evaluation and oversight is similarly weak in many jurisdictions (Cihon et al., 2021). Governments struggle to attract and retain the expertise needed to regulate powerful AI models, anc technically literate, governance-aware professionals may be the most serious constraint on effective AI governance (Dafoe, 2023; Reuel & Bucknall, 2024). Much of the existing talent is concentrated in a few dominant firms, limiting public-sector oversight and reinforcing asymmetries in governance capacity (Brennan et al., 2025).

Coordination costs escalate faster than capabilities. Each additional stakeholder, requirement, and review process adds friction to AI development (Schuett, 2023). While some friction helps ensure safety, excessive bureaucracy can drive development to less responsible actors or underground entirely (Zhang et al., 2025). Speed mismatches create fundamental governance gaps. AI capabilities advance in months while international agreements take years to negotiate (Grace et al., 2024). GPT-4's capabilities surprised experts in March 2023; by the time regulatory responses emerged in 2024, the technology had moved on to multimodal systems and AI agents (Casper et al., 2024). Safety researchers emphasize precaution and worst-case scenarios, companies prioritize competitive position and time-to-market, governments balance multiple constituencies with conflicting demands, and users want beneficial capabilities without understanding risks (Dafoe, 2023).

Regulatory arbitrage undermines safety standards across borders. If Europe implements strict safety requirements while other regions remain permissive, development may simply shift locations (Lancieri et al., 2024). As we previously discussed in the proliferation section, the digital nature of AI makes it so that a model can be trained in Singapore, deployed from Ireland, and used globally (Seger et al., 2023). Companies may bifurcate offerings, providing safer systems to regulated markets while deploying riskier versions elsewhere. True global coverage requires more than powerful individual jurisdictions.