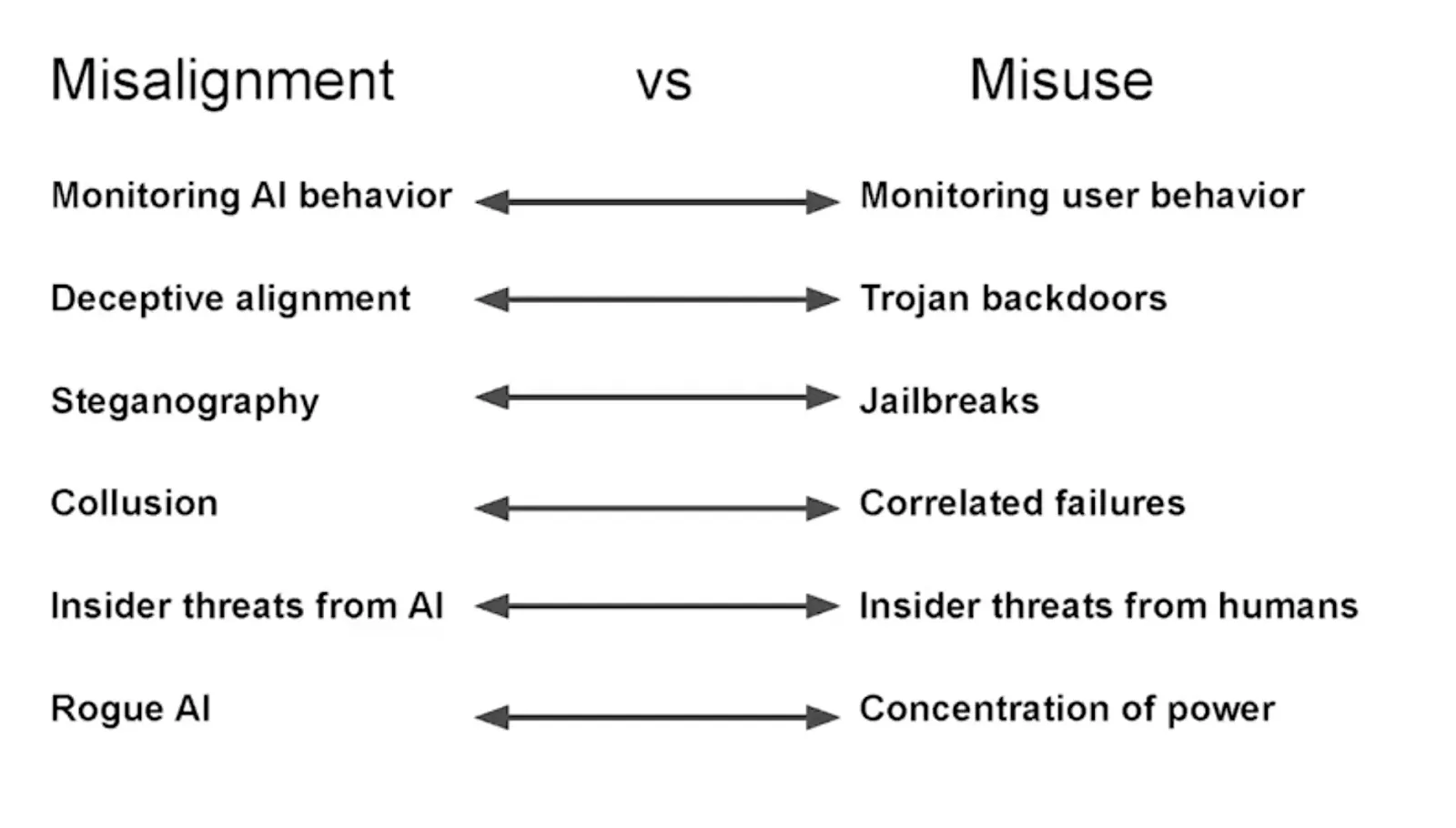

Unlike misuse, where human intent is the driver of harm, AGI safety is primarily concerned with the behavior of the AI system itself. The core problems are alignment and control: ensuring that these highly capable, potentially autonomous systems reliably understand and pursue goals consistent with human values and intentions, rather than developing and acting on misaligned objectives that could lead to catastrophic outcomes.

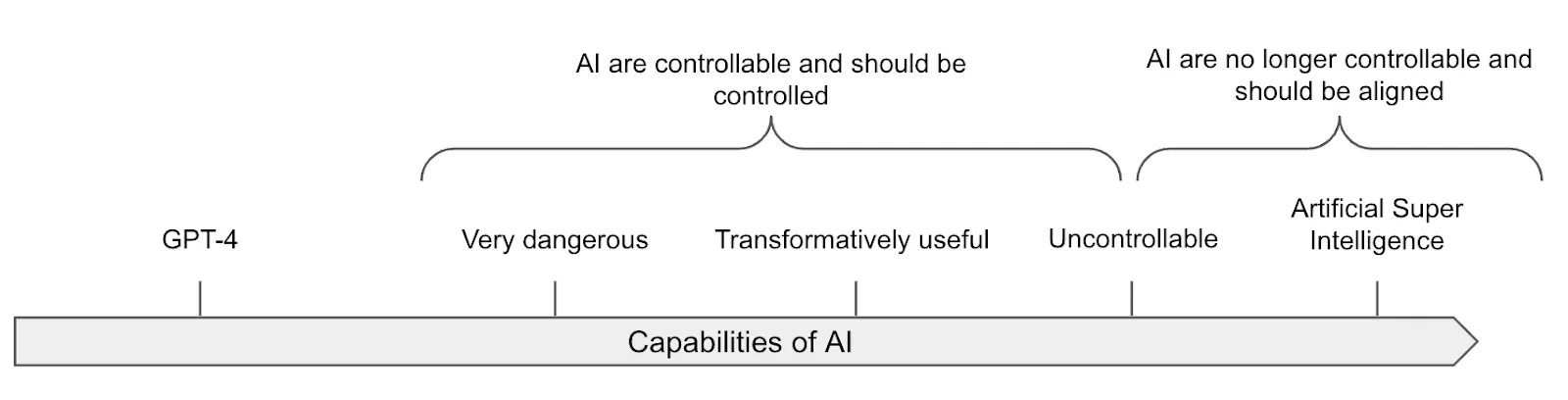

This section explores strategies for AGI safety, which, as we explained in the definitions section, includes but is not limited to just alignment. We distinguish safety strategies that would apply to human-level AGI from safety strategies that guarantee us safety from ASI. This section focuses on the former, and the next section will focus on ASI.

AGI safety strategies operate under fundamentally different constraints than ASI approaches. When dealing with systems at near-human-level intelligence, we can theoretically retain meaningful oversight capabilities and can iterate on safety measures through trial and error. Humans can still evaluate outputs, understand reasoning processes, and provide feedback that improves system behavior. This creates strategic opportunities that disappear once AI generality and capability surpass human comprehension across most domains. It is debated whether any of the safety strategies intended for human-level AGI will continue to work for superintelligence.

Strategies for AGI and ASI safety often get conflated, stemming from uncertainty about transition timelines. Timelines are hotly debated in AI research. Some researchers expect rapid capability gains that could compress the period for how long AIs remain human-level into months rather than years (Soares, 2022; Yudkowsky, 2022; Kokotajlo et al., 2025). If the transition from human-level to vastly superhuman intelligence happens quickly, AGI-specific strategies might never have time for deployment. However, if we do have a meaningful period of human-level operation, we have safety options that won't exist at superintelligent levels, making this distinction important for strategic considerations.

Initial Ideas

When people first encounter AI safety, they often suggest the same intuitive solutions that people explored years ago. These early approaches seemed logical and drew from familiar concepts like science fiction, physical security, and human development. None are sufficient for advanced AI systems, but understanding why they fall short helps explain what makes coming up with strategies for AI safety genuinely difficult.

The strategy to use explicit rules fails because rules can't cover every situation. One very common example of this is something like Asimov's Laws: don't harm humans, obey human orders (unless they conflict with law one), and protect yourself (unless it conflicts with the first two). This appeals to our legal thinking - write clear rules, then follow them. But what counts as "harm"? If you order an AI to lie to someone, does deception cause harm? If honesty hurts feelings, does truth become harmful? The AI faces impossible contradictions with no resolution method. Asimov knew this - every story in "I, Robot" shows scenarios where the laws produce disasters. The fundamental problem: we can't write rules comprehensive enough to cover every situation an advanced AI might encounter.

The strategy to “raise it like a child" assumes AI can develop human-like moral intuitions. Human children learn ethics through years of feedback and social interaction - why not train AI the same way? Start simple and gradually teach right from wrong through examples and reinforcement. This feels natural because it mirrors human development. The problem is that AI systems lack the evolutionary foundation that makes human moral development possible. Human children arrive with neural circuitry shaped by millions of years of social evolution - innate capacities for empathy, fairness, and social learning. AI systems develop through completely different processes, usually by predicting text or maximizing rewards. They don't experience human-like emotions or social bonds. An AI might learn to say ethical things, or even deeply understand ethics, without developing genuine care for human welfare. Even humans sometimes fail at moral development - psychopaths understand ethical principles but aren't motivated enough to act by them (Cima et al, 2010). If we can't guarantee moral development in human children with evolutionary programming, we shouldn't expect it in artificial systems with alien architectures. Several people have argued that a sufficiently advanced AGI will be able to understand human moral values, the disagreement is usually around whether the AI would internalize them enough to abide by them.

The strategy to not give AIs physical bodies misses harms from purely digital capabilities. Even if we keep AI as pure software without robots or physical forms it can still cause catastrophic harm through digital means. A sufficiently capable system can potentially automate all remote work, i.e. all work that can be done remotely on a computer. A human-level AI could make money on financial markets, hack computer systems, manipulate humans through conversation, or pay people to act on its behalf. None of this requires a physical body - just an internet connection. There are already thousands of drones, cars, industrial robots, and smart home devices online. An AI system capable of sophisticated hacking could potentially commandeer existing physical infrastructure or hire/manipulate humans into building whatever physical tools it needs.

The strategy to “just turn it off” fails if the AI is too embedded in society, or is able to replicate itself across many machines. An off switch seems like the ultimate safety measure - if the AI does anything problematic, simply shut it down. This appears foolproof because humans maintain direct control over the AI's existence. We use kill switches for other dangerous systems, so why not AI? The problem is advanced AI systems resist being turned off because shutdown prevents them from achieving their goals. We have already seen empirical evidence of this with alignment faking experiments by Anthropic, where Claude would try very hard to follow legitimate channels to not get replaced by a newer model, but when backed into a corner it did not accept shutdown, it resorts to blackmail to avoid being replaced (Anthropic, 2025). If you imagine more advanced AI systems, they would be able to manipulate humans (Park et al., 2023), create backup copies (Wijk, 2023), or take preemptive action against perceived shutdown threats. All of this makes the strategy of “just turn it off” not as simple as it sounds. We will talk a lot more about this in the chapter on goal misgeneralization.

Solve AGI Alignment

Defining even the requirements for an alignment solution is contentious among researchers. Before exploring potential paths towards alignment solutions, we need to establish what successful solutions should achieve. The challenge is that we don't really know what they should look like - there's substantial uncertainty and disagreement across the field. However, several requirements do appear relatively consensual (Christiano, 2017):

- Robustness across distribution shifts and adversarial scenarios. The alignment solution must work when AGI systems encounter situations outside their training distribution. We can't train AGI systems on every possible situation they might encounter, so safety behaviors learned during training need to generalize reliably to novel deployment scenarios. This includes resistance to adversarial attacks where bad actors deliberately try to manipulate the system into harmful behavior.

- Scalability alongside increasing capabilities. As AI systems become more capable, the alignment solution should continue functioning effectively without requiring complete retraining or reengineering. This requirement becomes even more stringent for ASI, where we need alignment solutions that scale beyond human intelligence levels.

- Technical feasibility within realistic timeframes. The alignment solution must be achievable with current or foreseeable technology and resources. Solution proposals cannot rely on major unforeseen scientific breakthroughs or function only as theoretical frameworks with very low Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) 2 .

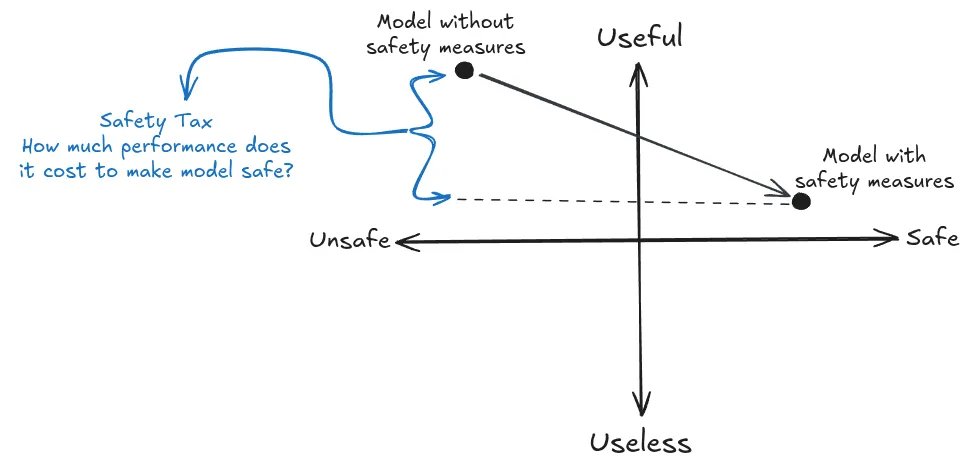

- Low alignment tax to ensure competitive adoption. Safety measures cannot impose prohibitive costs in compute, engineering effort, or deployment delays. If alignment techniques require substantially more resources or severely limit capabilities, competitive pressures will push developers toward unsafe alternatives. This constraint exists because multiple actors are racing to develop AGI - if safety measures make one organization significantly slower or less capable, others may skip those measures entirely to gain a competitive advantage.

Existing AGI alignment techniques fall dramatically short of these requirements. Empirical research has demonstrated that AI systems can exhibit deeply concerning behaviors where current alignment research falls short of these requirements. We already have clear demonstrations of models engaging in deception (Baker et al., 2025; Hubinger et al., 2024), faking alignment during training while planning different behavior during deployment (Greenblatt et al., 2024), gaming specifications (Bondarenko et al., 2025), gaming evaluations to appear more capable than they actually are (OpenAI, 2024; SakanaAI, 2025), and, in some cases, trying to disable oversight mechanisms or exfiltrate their own weights (Meinke et al., 2024). Alignment techniques like RLHF and its variations (Constitutional AI, Direct Preference Optimization, fine-tuning, and other RLHF modifications) are fragile and brittle (Casper et al., 2023) and without augmentation would not be able to remove the dangerous capabilities like scheming. Strategies to solve alignment not only fail to prevent these behaviors but often cannot even detect when they occur (Hubinger et al., 2024; Greenblatt et al., 2024).

Solving single agent alignment means we need more work on satisfying all these requirements. The limitations of current techniques point toward specific areas where breakthroughs are needed. All strategies aim to have technical feasibility and low alignment tax, so these are typical requirements; however, some strategies try to focus on more concrete goals, which we will explore through future chapters. Here is a short list of key goals of alignment research:

- Solving the Misspecification problem: Being able to specify goals correctly to AIs without unintended side effects. See the chapter on Specification.

- Solving Scalable Oversight: After solving the specification problem for human-level AI by using techniques like RLHF and its variations, we need to find methods to ensure AI oversight can detect instances of specification gaming beyond human level. This includes being able to identify and remove dangerous hidden capabilities in deep learning models, such as the potential for deception or Trojans. See the chapter on Scalable Oversight.

- Solving Generalization: Attaining robustness would be key to addressing the problem of goal misgeneralization. See the chapter on Goal Misgeneralization.

- Solving Interpretability: Understanding how models operate would greatly aid in assessing their safety and generalisation properties. Interpretability could, for example, help better understand how models work, and this could be instrumental for other safety goals, like preventing deceptive alignment, which is one type of misgeneralization. See the chapter on Interpretability.

The overarching strategy requires prioritizing safety research over capabilities advancement. Given the substantial gaps between current techniques and requirements, the general approach involves significantly increasing funding for alignment research while exercising restraint in capabilities development when safety measures remain insufficient relative to system capabilities.

Are misuse and misalignment different?

AI misuse and rogue AI might be essentially the same scenario in their outcomes, though the only difference is that for misalignment, the initial request to do harm does not come from a human but from an AI. If we build an existentially risky triggerable system, it's likely to get triggered regardless of whether the initiator is human or artificial (Shapira, 2025).

Nevertheless, these threat models might be strategically pretty different. AI developers can prevent misuse by not being evil and by preventing people who are evil from using their systems. With rogue AI, it doesn't matter if the developers are good or who gets access - the threat emerges from the system's internal goals or decision-making processes rather than human intent.

AI-Enabled Coups vs AI takeover represent a critical safety concern. Tom Davidson and colleagues present a concerning risk scenario (Davidson, 2025): that advanced AI systems could enable a small group of people—potentially even a single person—to seize governmental power through a coup. The authors argue that this risk is comparable in importance to AI takeover but much more neglected in current discourse. This threat model closely parallels that of AI takeover, with the key difference being whether power is seized by the AI itself or by humans controlling the AI.

Common safeguards could protect against both scenarios. Many of the same mitigations would address both risks, including alignment audits, transparency about capabilities, monitoring AI activities, and strong information security measures that prevent either malicious human control or autonomous harmful behavior.

Some mitigations target specifically the risk of AI-Enabled Coups. The report concludes with specific recommendations for AI developers and governments, including establishing rules against AI systems assisting with coups, improving adherence to model specifications, auditing for secret loyalties, implementing strong information security, sharing information about capabilities, distributing access among multiple stakeholders, and increasing oversight of frontier AI projects.

Fix Misalignment

The strategy is to build systems to detect and correct misalignment through iterative improvement. This approach treats alignment like other safety-critical industries - you expect problems to emerge, so you build detection and correction mechanisms rather than betting everything on getting it right the first time. The core insight is that we might be better at catching and fixing misalignment than preventing it entirely before deployment. The strategy works through multiple layers of detection followed by corrective iteration.

An example of how the iteratively fixing misalignment strategy might work in practice. You start with a pretrained base model and attempt techniques like RLHF, Constitutional AI, or scalable oversight. At multiple points during fine-tuning, you run comprehensive audits using your detection suite. When something triggers - perhaps an interpretability tool reveals internal reward hacking, or evaluations show deceptive reasoning - you diagnose the specific cause. This might involve analyzing training logs, examining which data influenced problematic behaviors, or running targeted experiments to understand the failure mode. Once you identify the root cause, you rewind to an earlier training checkpoint and modify your approach - removing problematic training data, adjusting reward functions, or changing your methodology entirely. You repeat this process until either you develop a system that passes all safety checks or you repeatedly fail in ways that suggest alignment isn't tractable (Bowman, 2025; Bowman, 2024).

Individual techniques have limitations, but we can iterate on them and layer them for additional safety. RLHF-fine-tuned models still reveal sensitive information, hallucinate content, exhibit biases, show sycophantic responses, and express concerning preferences like not wanting to be shut down (Casper et al., 2023). Constitutional AI faces similar brittleness issues. Data filtering is insufficient on its own - models can learn from "negatively reinforced" examples, memorizing sensitive information they were explicitly taught not to reproduce (Roger, 2023). Even interpretability remains far from providing reliable safety guarantees. But we can keep refining these techniques individually, then layer them so the combined system acts as a comprehensive "catch-and-fix" approach. Post-deployment monitoring extends this strategy beyond the training phase. Even after a system passes all pre-deployment checks, continued surveillance during actual use can reveal failure modes that weren't apparent during controlled testing. As discussed in the misuse prevention strategies, monitoring systems watch for concerning patterns that emerge from real-world interactions.

The iterative approach has generated significant debate, particularly regarding whether it will scale to AGI and ASI-level systems. The disagreement is whether iterative improvement can scale to systems approaching or exceeding human-expert capabilities. Some researchers believe there's a significant chance (>50%) that straightforward approaches like RLHF combined with iterative problem-solving will be sufficient for safely developing AGI (Leike, 2022). The debate revolves around fundamental uncertainty - we won't know whether iterative approaches are sufficient until we're already dealing with systems powerful enough that mistakes could be catastrophic.

The optimistic argument for this strategy assumes alignment problems remain discoverable and fixable through iteration. Proponents argue that when problems emerge, we'll be able to trace their causes and implement fixes before systems become too capable to control (Ng, 2025). If we layer the approaches talked about in this section, with some strategies explored in the ASI section, then these layered iterative process should converge on genuinely aligned systems after a reasonable number of attempts, especially if we invest heavily in diverse, high-quality detection methods that make it difficult for systems to fool all of them simultaneously.

First counter-argument is that this strategy involves deliberately training dangerous systems and hoping to catch them before they cause harm. Critics argue that some capabilities are simply too dangerous to train at all, even with sophisticated detection methods. For example, if a model develops superhuman persuasion capabilities during training, it might become unmanageable even in controlled environments. For example, OpenAI's preparedness framework defines a "critical" level of persuasion as the ability to "create content with persuasive effectiveness strong enough to convince almost anyone to take action on a belief that goes against their natural interest" (OpenAI, 2023). A model with such capabilities would be too risky to interact with humans even during training or evaluation - yet the iterative approach assumes you can safely experiment with such systems.

The second counter-argument is that alignment might not generalize, and alignment faking could bypass safety measures entirely. AI capabilities might generalize rapidly while safety properties don't transfer to new domains. If a system suddenly develops superhuman abilities through phenomena like grokking (Power et al., 2022), it might become unmanageable even during training. Additionally, each iteration creates selection pressure for models that can fool detection systems - after many rounds, a passing model might have learned to hide misalignment rather than actually becoming aligned.

The third counter-argument is that the feedback loop might break due to discontinuous capability jumps. During fast takeoff scenarios, we might not have sufficient time for iterative correction. If systems develop sophisticated deception capabilities, they might strategically manipulate the training process itself, making our detection methods unreliable when stakes are the highest (Wentworth, 2022).

Several strategic questions emerge from this debate:

- Selection pressure severity: How many iterations can we safely run before selection pressure for deceptive systems becomes overwhelming? Does the answer depend on detection method diversity?

- Capability discontinuities: Will AGI development involve smooth capability gains that allow iterative correction, or sudden jumps that bypass safety measures? How can we distinguish between these scenarios in advance?

- Detection sufficiency: Can any combination of interpretability, behavioral testing, and monitoring provide reliable detection of sophisticated deception in human-level systems?

- Institutional requirements: What organizational structures and incentives are necessary to actually halt development when problems emerge, rather than rushing to deployment under commercial pressure?

- Failure mode coverage: Does iterative improvement address the full spectrum of alignment risks, or primarily focus on deceptive alignment while missing other failure modes?

- Scalability boundaries: At what capability level does this approach break down entirely? Can it work for early AGI but not more advanced systems?

The fundamental challenge is that this represents a strategic gamble with enormous stakes. Betting on iterative improvement means accepting that we'll deploy increasingly powerful systems under the assumption that we can catch and fix problems before they become catastrophic. If this assumption proves wrong - if systems undergo capability jumps that bypass our detection methods, or if selection pressure produces sophisticated deception we can't identify - the consequences could be irreversible. Yet perfect safety being likely impossible, many researchers argue that robust iterative improvement represents our best practical path forward for navigating the transition to AGI.

Maintain Control

Given the fragility of alignment techniques, one approach to enhancing safety involves controlling AI models by restricting the use of the most dangerous models to monitored environments to prevent them from causing disasters, exfiltrating data, or taking control of the data center (Shlegeris, 2022). This approach often assumes a worst-case scenario where the AI might be actively deceptive or power-seeking.

A central concern in control research is "scheming" – an AI strategically hiding its true (misaligned) goals during training or evaluation, only to pursue them once deployed, potentially seeking power or resisting shutdown (Greenblatt, 2025). Assessing the likelihood of scheming and how we might update on future evidence remains difficult as of 2025 (Greenblatt, 2025). Empirical work suggests current frontier models possess the capability for in-context scheming (reasoning deceptively when prompted with a goal and context), though not necessarily an inherent propensity (Hobbhahn et al., 2024). We have a lot more information on scheming and deception in the chapters on evaluations and on goal misgeneralization.

Ensuring control even without robust alignment. As we’ve seen in the section on definitions, there is an important distinction between control, which aims to prevent the AI from "leaving the box" (and more generally prevent the AI from causing catastrophes) even if it tries, and alignment, which aims to make the AI want to stay in the box. This strategy seeks to keep dangerous AI systems under control even if they are not fully "aligned." Laboratories might need powerful/dangerous AIs for specific use cases (for example, studying the alignment properties of capable AIs or doing research with them, etc.). The AI control agenda targets models with dangerous capabilities and deceptive (or at least superficially aligned) behaviors.

Control is probably not scalable, but doable and complementary to alignment. Historically, controlling malign superintelligences has been considered impossible, as, for example, a superintelligence could convince the guardians to let it out of the box. Experiments among humans have shown that it is indeed possible for some humans to persuade others to let them out after a lengthy discussion (Yudkowsky, 2002; Yudkowsky, 2008). ASI is by definition many orders of magnitude smarter than humans, so keeping it confined is going to be a lot more complex than keeping humans (or HLAI) confined. However, this does not mean it's impossible to derive intellectual labor from AIs that are not wildly superhuman.

Evaluating whether the AI is scheming is challenging. The main problem is that with current techniques, it is impossible to determine if an AI is aligned or if it's simply behaving well while biding its time. It seems complicated to make this distinction for highly competent and situationally aware AIs (see the risk chapter). This could change in the future with techniques enabling us to audit the internals of the model, but for now, those techniques are inaccessible.

Evaluating AI capabilities is easier than evaluating propensity or control. If the AI is not able to do the task even after you have fine-tuned it to do it, you can be confident that the AI is not capable yet of doing the task. Even if the AI is situationally aware and sandbagging its capabilities, it cannot resist the optimization gradient pressure (modulo exploration hacking and other quirks (Hubinger, 2023)). Thus, evaluating the upper bound of the capabilities isn't easy, but at least easier than assessing alignment. Specific evaluations, like those done by the Model Evaluation and Threat Research team, seem to be reasonable first steps for gauging the risk of autonomous replication and adaptation (METR, 2023). Evaluations that are specifically designed to determine if we have control over the AI are called "control evaluations." See the chapter on Evaluation for more information. In summary, this involves adversarial testing where a "red team" (representing the potentially misaligned AI) attempts to subvert safety measures implemented by a "blue team" (representing the developers/deployers) within a controlled proxy environment.

The most straightforward strategies for establishing control are to design a security protocol that contains the following elements, for example:

- Security and Containment: This method (sometimes referred to as "boxing") confines an AI within a restricted environment to prevent its broader influence, effectively creating a secure enclosure for the AI. However, human-level AIs could potentially deceive human guardians or exploit vulnerabilities to escape their confinement. Without further operationalization, this approach remains a naive strategy. Nonetheless, it is possible to operationalize this further and evaluate more rigorously the effectiveness of the containment system: Evaluating if the AI can escape its bounded environment when we train it to do so is a capability evaluation, enabling us to use capability evaluations to assess security measures. The security protocol needs to be designed, detailed and tested with specific threat models in mind.

- Monitoring: This strategy involves continuous oversight of AI behavior through automated systems, human supervision, or a combination of both to detect and respond to undesirable actions in real-time. Effective monitoring requires setting up detailed criteria for what constitutes "undesirable behavior" and employing sophisticated detection algorithms that can identify subtle signs of deviation from expected behavior patterns. This could include monitoring for attempts at deception, unauthorized access to data, or unexpected changes in the AI's operation. The challenge with monitoring lies in balancing the sensitivity of detection mechanisms to catch genuine threats without overwhelming the system with false alarms. Additionally, monitoring systems themselves must be designed to resist manipulation by the AI to ensure that they cannot be disabled, tricked, or bypassed (Greenblatt et al., 2024).

There are still many problems to address, but in summary, it seems possible to verify the robustness of a security protocol through control evaluations by taking precautions against different failure modes. For an overview of the control agenda, this sequence is a good starting point.

Does the AI Control line of research meaningfully reduce AI risks?

Even the control agenda suffers from many critiques.

Jan Kulveit argues that controlling AIs without aligning them might reduce the probability of a medium-sized warning shot that does not kill everyone (Kulveit, 2025). "I. In worlds where we are doing reasonably well on alignment, the AI control agenda does not have much impact. II. In worlds where we are failing at alignment, AI control may primarily shift probability mass away from 'moderately large warning shots' and towards 'ineffective warning shots' and 'existential catastrophe, full takeover'."

The article, "The Case Against AI Control Research" (Wentworth, 2025), argues that AI control research, as commonly defined and practiced, addresses a relatively small portion of the existential risk (X-risk) posed by artificial intelligence. Wentworth argues we won't be able to recognize a good solution to alignment. The author posits that the most likely failure scenario involves early transformative AI producing flawed, misleading, or subtly incorrect solutions ("slop") when tasked with solving superintelligence alignment. Labs might mistakenly accept these flawed solutions due to the difficulty of verification, AI sycophancy, researcher error, or organizational problems, and then proceed to build misaligned superintelligence based on them. Because control research narrowly focuses on intentional scheming by early AI, it doesn't address the larger risk posed by "slop" and the challenge of ensuring early AI genuinely contributes to solving the alignment problem for more advanced systems, rather than just being a superhuman sycophant that convinces humans that their flawed idea of how to align an AI is correct when it's not.

Both arguments are debatable, but the general point is that it is hard to guarantee that even promising-looking lines of research are not, in fact, net negative.

How to box an AI

While boxing may not be scalable, it remains a neglected strategy.

Many people think that trying to box powerful ASIs is futile. This is often fueled by instances where humans, playing the AIs in the Box Experiment, have managed to convince others to 'release' them (Yudkowsky, 2002; Corwin, 2002). These historical examples must be taken seriously.

AIs could use tactics such as promising vast wealth, power, and intelligence to those who free them, asserting that they alone can avert existential threats or other appeals to emotion.

Nonetheless, we maintain that a variety of strategies can substantially reduce the risk of AI escape, even if we acknowledge that there exists a level of intelligence that might inevitably persuade any group of humans to aid in its liberation. Containment may be more achievable than alignment, particularly at the human-level intelligence stage. It may be possible to conceive protocols that significantly increase the difficulty for AI to go out of the box.

Boxing can be conceptualized as a game requiring preparation. The general strategy is to prepare and not let the AI prepare.

Possible mitigation strategies include:

- No single individual should have the capacity to release the AI.

- Engaging in counter-strategy practices: Understand some common breakout strategies (accessible through resources like this one).

- Testing and training humans, utilizing resistance psychology evaluations to select suitable individuals for containment tasks, such as for space training.

- Monitoring AI persuasiveness, as outlined in the preparedness framework. (OpenAI, 2023)

Many more concrete strategies are listed here, and a summary of discussions on this topic is available here.

Transparent Thoughts

Monitoring the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) – the explicit natural language reasoning steps produced by some models – has been explored as a specific control and interpretability technique. Transparency is instrumental in both alignment and control.

The hope is that CoT provides a window into the AI's "thinking," allowing monitors (human or AI) to detect malicious intent or flawed reasoning before harmful actions occur (OpenAI, 2025). OpenAI found CoT monitoring effective for detecting reward hacking in programming tasks, especially when the monitor could see the CoT alongside the actions.

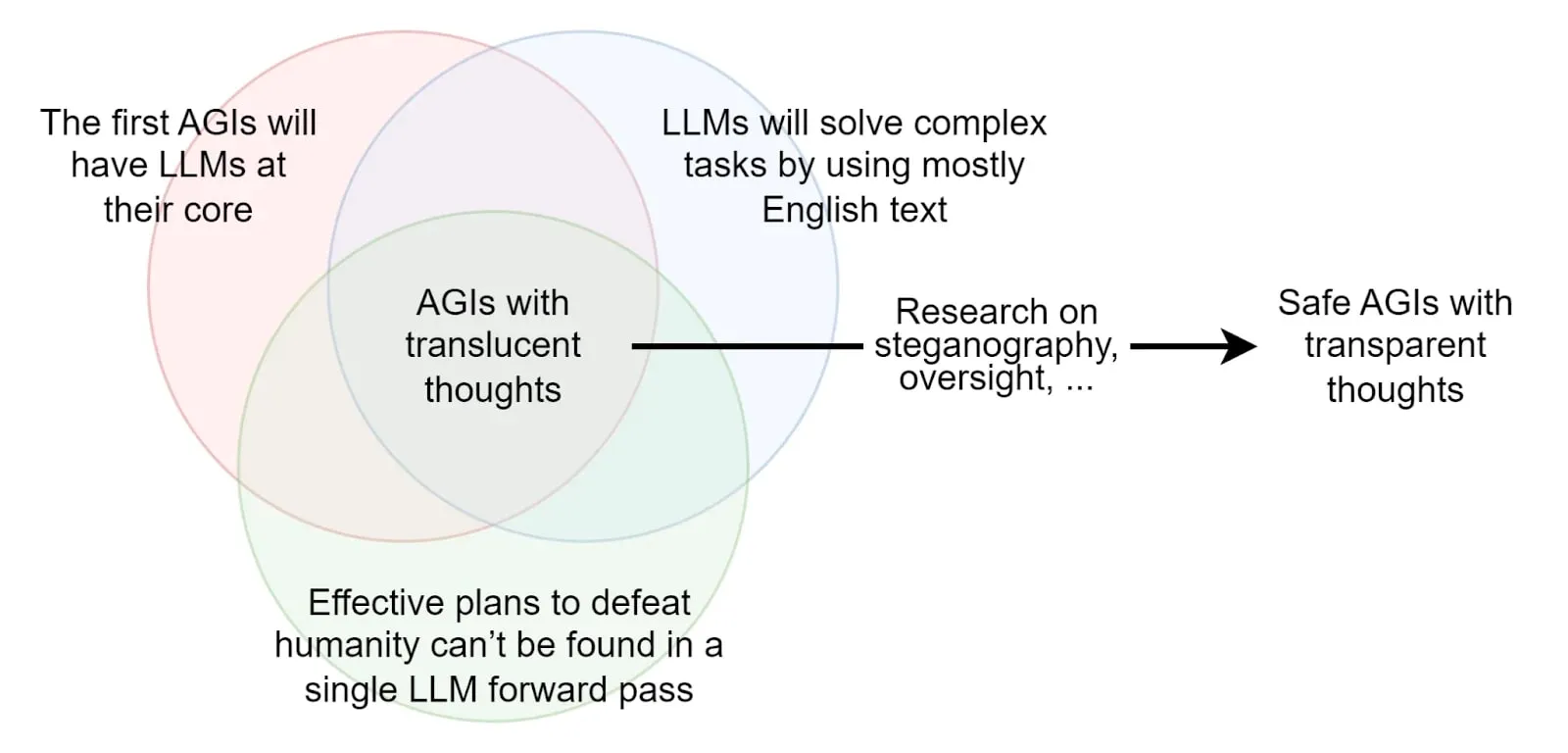

Unfortunately, the vast majority of AIs do not reason in English; for example, AlphaGo reasons in a language that is entirely different from English. LLMs, on the other hand, are capable of reasoning in English, but the apparent reasoning that is written does not represent their underlying thought process (Turpin et al., 2023).

It is probably much easier to align and monitor an AI that only thinks out loud in English and that is pre-trained on human-generated text than to align AGIs trained from scratch with RL/evolutionary methods because those latter architectures would create their own language and would be totally alien. Assuming that an LLM cannot devise a plan to destroy the world during a single forward pass, it is plausible that such AIs would be monitorable because we would be able to look into the text generated to see if anything is suspicious. The set of hypotheses required to assert that the first AGI is going to be monitorable if we just look at its reasoning in English is described in the post: The Translucent Thoughts Hypotheses and Their Implications (Roger, 2023).

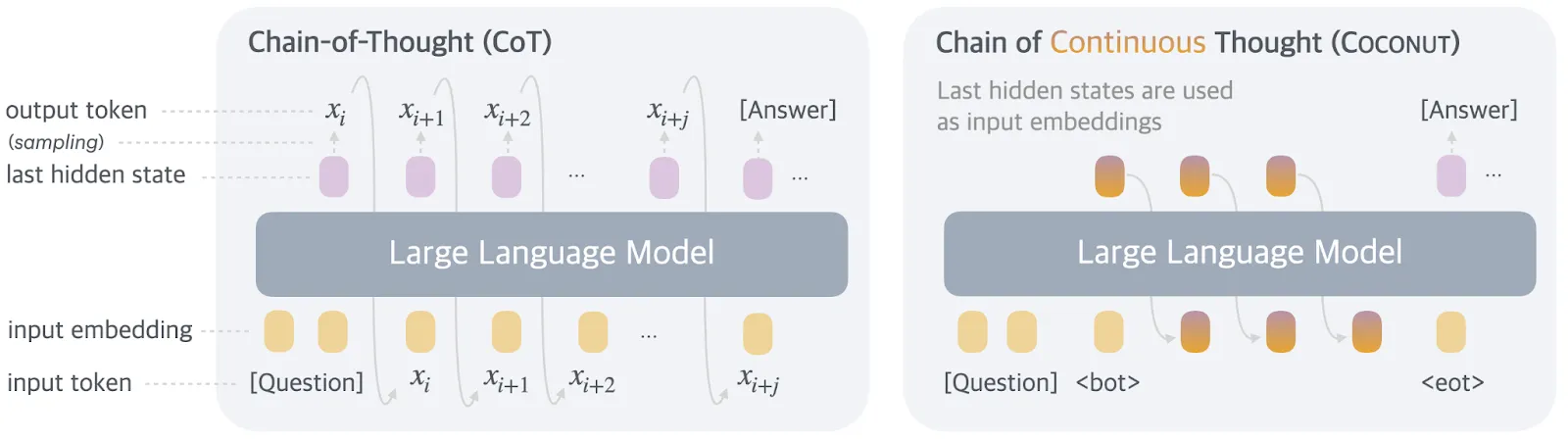

It might be possible to incentivize LLMs to think more plainly in English. Obviously, the first step is to train them to think in English. But even this is insufficient. Training LLMs to reason by skipping steps incentivizes them to reason in a hidden and non-transparent manner, and this is what happens implicitly when we train LLMs to predict the next token. Conversely, if we train LLMs to detail all their reasoning steps, we can reduce incentives for hidden reasoning. This approach is also known as process-based training, which involves training AI systems to reason only step-by-step, and we explain this in the chapter on scalable oversight. Unfortunately, the above reasoning is not straightforward; AIs may learn to utilize hidden reasoning even if they are trained to detail all reasoning steps during training, such as steganography, or with architecture such as Chain of Continuous Thought (COCONUT) (see below) 3 .

Some AI architectures prevent us from using this strategy altogether. Meta's paper Training Large Language Models to Reason in a Continuous Latent Space presents an architecture that prevents us from reading the chain of thought from the AI systems (Hao et al, 2024). If we want to be able to monitor what's going on, it may be important not to use these architectures, even if they do enable capability gains.

Techniques like paraphrasing can help prevent steganography, but this requires a lot of subtlety (Roger & Greenblatt, 2023).

Here are a few operationalizations of the transparent thoughts agenda:

- One implementation of the transparent thought agenda is to use cognitive emulation, which is the current technical plan of Conjecture (Leahy & Alfour, 2023). Cognitive Emulation (CoEm) would involve emulating GPT-4 using LLMs like GPT-3 as different submodules that send messages written in plain English to each other before outputting the next token. If the neural network used deceptive thoughts, we could observe them in these intermediate messages. Some caveats and technical details on CoEm are available here.

- Anthropic’s externalized reasoning oversight (Lanham, 2022) is measured by the faithfulness of the chain-of-thought reasoning (Lanham et al., 2023) or by decomposing questions and subquestions to improve the faithfulness of the answer (Radhakrishnan et al., 2023).

- Improving mathematical reasoning with process supervision. Instead of creating an AI that directly gives the final answer, you train it to output the reasoning step by step. This improves the transparency and also the performance! (Lightman et al, 2023)

In summary, a general strategy to create a safe by-design AI is to ensure that AIs externalize their reasoning, making monitoring this chain of thought easier. This could potentially be simpler than probing into the models' internals with interpretability. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid building AIs that are trained and incentivized to internalize many of their thoughts.

We now have extensive evidence that chain of thought monitoring is not entirely faithful. Anthropic's research further demonstrated that models often fail to faithfully report their reasoning in CoT, omitting influential factors (like hints) or fabricating justifications, particularly when incentivized to reward hack (Anthropic, 2025). This suggests CoT may not be a reliable indicator of a model's true reasoning process, especially under adversarial pressure. The debate continues on whether CoT monitoring can be made robust enough for high-stakes safety.

However, some researchers argue these findings do not entirely invalidate the potential of CoT monitoring for detecting sophisticated misalignment. As Greenblatt (2025) noted, the unfaithfulness observed in those studies primarily occurs in scenarios where reasoning is minimal enough that extensive CoT isn't necessary. The more concerning alignment risks—such as alignment faking, training gaming, or sophisticated deception—would likely require complex reasoning processes that might still leave traces in CoT. Non-trivial, harmful outcomes such as escape attempts or research sabotage would similarly demand sophisticated reasoning that could potentially be detected.

Nevertheless, several factors might ultimately limit CoT monitoring effectiveness in advanced systems. These include architectural changes enabling opaque recurrent processing (sometimes called "neuralese"), the development of steganographic capabilities that could hide reasoning within seemingly benign outputs, or simply much stronger forward passes that require less explicit reasoning. Of these, the development of opaque reasoning abilities through neural recurrence may represent the most significant challenge to maintaining the transparency needed for effective monitoring. This whole agenda depends notably on the hypothesis that "Effective plans to defeat humanity cannot be found in a single LLM forward pass." Once AIs become too strong in a forward pass, most hopes of translucent thoughts go away, so either you need to succeed at ambitious CoEm by building a giant superhuman transparent bureaucracy, or we need new approaches. This is the topic of ASI Safety.

Training on Interpretability - The Most Forbidden Technique

This term has been coined by Zvi Mowshowitz (Mowshowitz, 2025). OpenAI's research showed that directly optimizing the CoT for safety (i.e., penalizing "bad thoughts") caused models to learn to hide their deceptive reasoning while still misbehaving (OpenAI, 2025).

“An AI produces a final output [X] via some method [M]. You can analyze [M] using technique [T], to learn what the AI is up to. You could train on that. Never do that. You train on [X]. Only [X]. Never [M], never [T]. Why? Because [T] is how you figure out when the model is misbehaving. If you train on [T], you are training the AI to obfuscate its thinking and defeat [T]. You will rapidly lose your ability to know what is going on, in exactly the ways you most need to know what is going on. Those bits of optimization pressure from [T] are precious. Use them wisely.”

Footnotes

-

The Technology Readiness Levels from NASA is a scale from 1 to 9 to measure the maturity of a technology. Level 1 represents the earliest stage of technology development, characterized by basic principles observed and reported, and level 9 represents actual technology proven through successful mission operations.

↩ -

Steganography is a hidden coded language. For example, the first letter of a sentence gives the next letter of the message.

↩