Takeoff speed refers to how quickly AI systems become dramatically more powerful than they are today and cause major societal changes. This is related to, but distinct from, AI timelines (how long until we develop advanced AI). While timelines tell us when transformative AI might arrive, takeoff speeds tell us what happens after it arrives - does AI capability and impact increase gradually over years, or explosively over days or weeks?

How can we think about different takeoff speeds? When analyzing different takeoff scenarios, we can look at several key factors:

- Speed: How quickly do AI capabilities improve?

- Continuity: Do capabilities improve smoothly or in sudden jumps?

- Homogeneity: How similar are different AI systems to each other?

- Polarity: How concentrated is power among different AI systems?

In the next section we discuss just one of these factors that tends to be the most discussed aspect - takeoff speed. The rest are explained in the appendix.

Speed

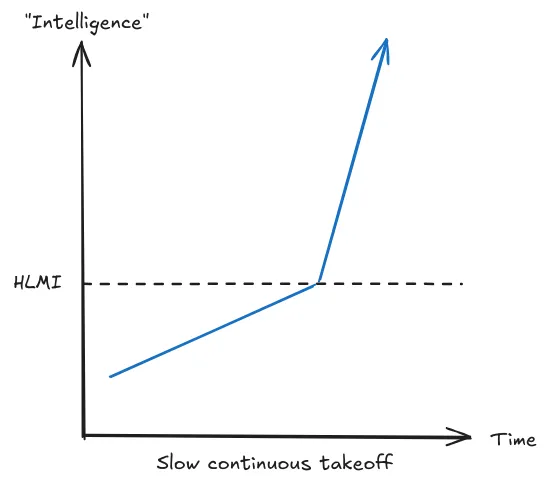

What is a slow takeoff? In a slow takeoff scenario, AI capabilities improve gradually over months or years. We can see this pattern in recent history - the transition from GPT-3 to GPT-4 brought significant improvements in reasoning, coding, and general knowledge, but these advances happened over several years through incremental progress. Paul Christiano describes slow takeoff as similar to the Industrial Revolution but "10x-100x faster" (Davidson, 2023). Terms like "slow takeoff" and "soft takeoff" are often used interchangeably.

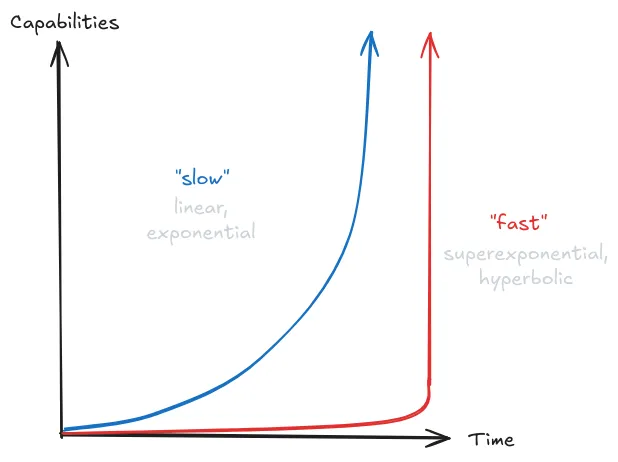

In mathematical terms, slow takeoff scenarios typically show linear or exponential growth patterns. With linear growth, capabilities increase by the same absolute amount each year - imagine an AI system that gains a fixed number of new skills annually. More commonly, we might see exponential growth, where capabilities increase by a constant percentage, similar to how we discussed scaling laws in earlier sections. Just as model performance improves predictably with compute and data, slow takeoff suggests capabilities would grow at a steady but manageable rate. This might manifest as GDP growing at 10-30% annually before accelerating further.

The key advantage of slow takeoff is that it provides time to adapt and respond. If we discover problems with our current safety approaches, we can adjust them before AI becomes significantly more powerful. This connects directly to what we'll discuss in later chapters about governance and oversight - slow takeoff allows for iterative refinement of safety measures and gives time for coordination between different actors and institutions.

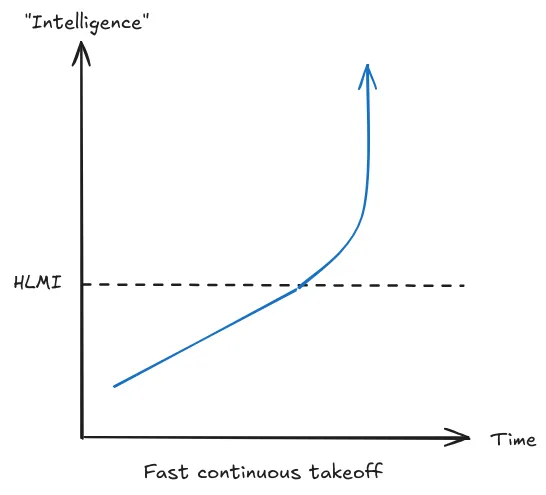

What is a fast takeoff? Fast takeoff describes scenarios where AI capabilities increase dramatically over very short periods - perhaps days or even hours. Instead of the gradual improvement we saw from GPT-3 to GPT-4, imagine an AI system making that much progress every day. This could happen through recursive self-improvement, where an AI system becomes better at improving itself, creating an accelerating feedback loop.

Mathematically, fast takeoff involves superexponential or hyperbolic growth, where the growth rate itself increases over time. Rather than capabilities doubling every year as in exponential growth, they might double every month, then every week, then every day. This relates to what we discussed in the scaling section about potential feedback loops in AI development - if AI systems can improve the efficiency of AI research itself, we might see this kind of accelerating progress.

The dramatic speed of fast takeoff creates unique challenges for safety. As we'll explore in the chapter on strategies, many current safety approaches rely on testing systems, finding problems, and making improvements. But in a fast takeoff scenario, we might only get one chance to get things right. If an AI system starts rapidly self-improving, we need safety measures that work robustly from the start, because we won't have time to fix problems once they emerge.

Terms like "fast takeoff", "hard takeoff" and "FOOM" are often used interchangeably.

Why does takeoff speed matter for AI risk? The speed of AI takeoff fundamentally shapes the challenge of making AI safe. This connects directly to what we discussed about scaling laws and trends - if progress follows predictable patterns as our current understanding suggests, we might have more warning and time to prepare. But if new mechanisms like recursive self-improvement create faster feedback loops, we need different strategies.

A simplistic example helps illustrate this: Today, when we discover that language models can be jailbroken in certain ways, we can patch these vulnerabilities in the next iteration. In a slow takeoff, this pattern could continue - we'd have time to discover and fix safety issues as they arise. But in a fast takeoff, we might need to solve all potential jailbreaking vulnerabilities before deployment, because a system could become too powerful to safely modify before we can implement fixes.

Understanding fast vs slow helps you get the gist of the takeoff debate, but there can be a bunch of other factors like continuity, similarity and polarity at play. If you want to learn more feel free to read the optional details on these in the appendix.

Takeoff Arguments

The Overhang Argument. There might be situations where there are substantial advancements or availability in one aspect of the AI system, such as hardware or data, but the corresponding software or algorithms to fully utilize these resources haven't been developed yet. The term 'overhang' is used because these situations imply a kind of 'stored’ or ‘latent’ potential. Once the software or algorithms catch up to the hardware or data, there could be a sudden unleashing of this potential, leading to a rapid leap in AI capabilities. Overhangs provide one possible argument for why we might favor discontinuous or fast takeoffs. There are two types of overhangs commonly discussed:

- Hardware Overhang: This refers to a situation where there is enough computing hardware to run many powerful AI systems, but the software to run such systems hasn't been developed yet. If such hardware could be repurposed for AI, this would mean that as soon as one powerful AI system exists, probably a large number of them would exist, which might amplify the impact of the arrival of human-level AI.

- Data Overhang: This would be a situation where there is an abundance of data available that could be used for training AI systems, but the AI algorithms capable of utilizing all that data effectively haven't been developed or deployed yet.

Overhangs are also used as a counter argument to why AI pauses do not affect takeoff. One counter argument to the overhang argument is that it relies on the assumption that during the time that we are pausing AI development, the rate of production of chips will remain constant. It could be argued that the companies manufacturing these chips will not make as many chips if data centers aren't buying them. However, this argument only works if the pause is for any appreciable length of time, otherwise the data centers might just stockpile the chips. It is also possible to make progress on improved chip design, without having to manufacture as many during the pause period. However, during the same pause period we could also make progress on AI safety techniques (Elmore, 2024).

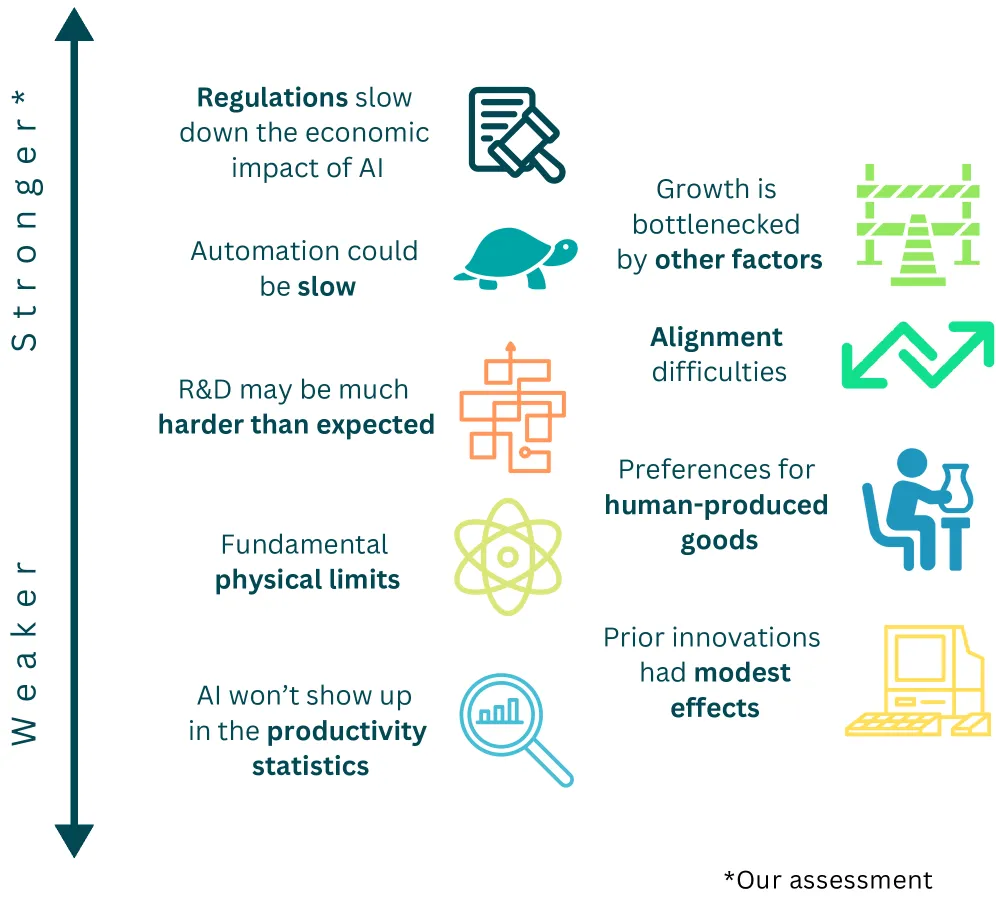

The Economic Growth Argument. Historical patterns of economic growth, driven by human population increases, suggest a potential for slow and continuous AI takeoff. This argument says that as AIs augment the effective economic population, we might witness a gradual increase in economic growth, mirroring past expansions but at a potentially accelerated rate due to AI-enabled automation. Limitations in AI's ability to automate certain tasks, alongside societal and regulatory constraints (e.g. that medical or legal services can only be rendered by humans), could lead to a slower expansion of AI capabilities. Alternatively, growth might far exceed historical rates. Using a similar argument for a fast takeoff hinges on AI's potential to quickly automate human labor on a massive scale, leading to unprecedented economic acceleration.

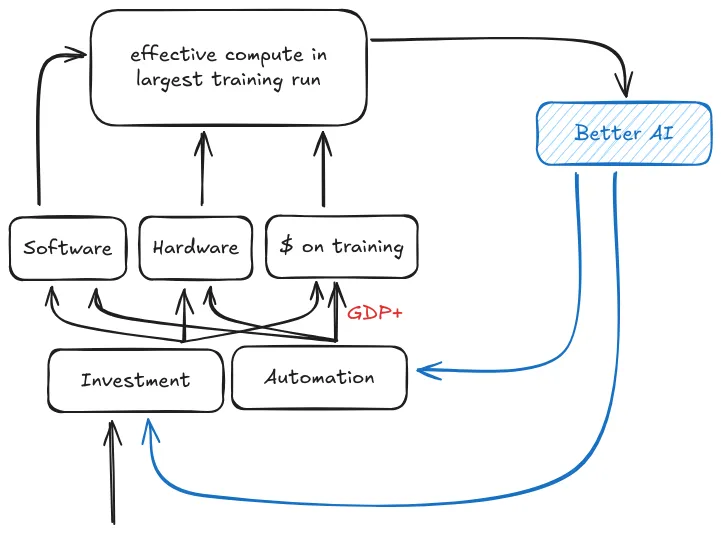

Compute Centric Takeoff Argument. This argument, similar to the Bio Anchors report, assumes that compute will be sufficient for transformative AI. Based on this assumption, Tom Davidson's 2023 report on compute-centric AI takeoff discusses feedback loops that may contribute to takeoff dynamics.

- Investment feedback loop: There might be increasing investment in AI, as AIs play a larger and larger role in the economy. This increases the amount of compute available to train models, as well as potentially leading to the discovery of novel algorithms. All of this increases capabilities, which drives economic progress, and further incentivizes investment.

- Automation feedback loop: As AIs get more capable, they will be able to automate larger parts of the work of coming up with better AI algorithms, or helping in the design of better GPUs. Both of these will increase the capability of the AIs, which in turn allow them to automate more labor.

Depending on the strength and interplay of these feedback loops, they can create a self-fulfilling prophecy leading to either an accelerating fast takeoff if regulations don't curtail various aspects of such loops, or a slow takeoff if the loops are weaker or counterbalanced by other factors. The entire model is shown in the diagram below:

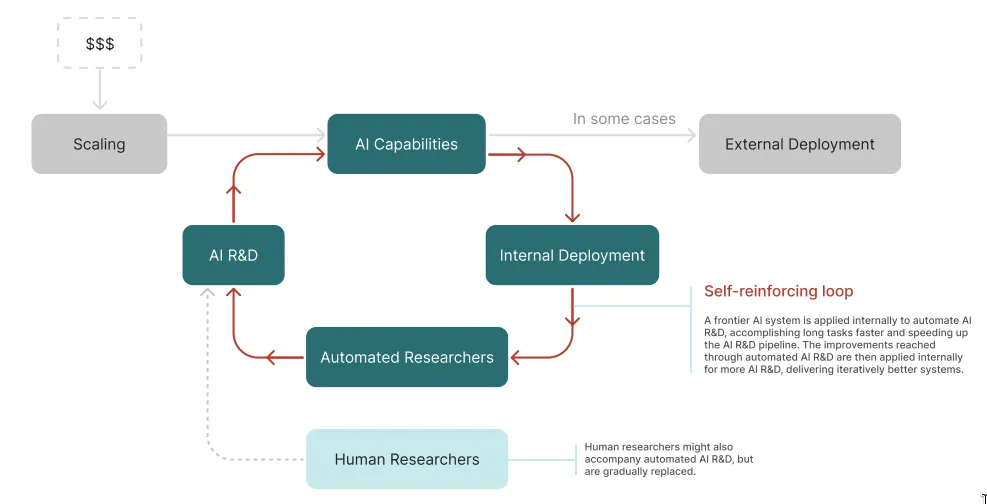

Automating Research Argument. Researchers could potentially design the next generation of ML models more quickly by delegating some work to existing models, creating a feedback loop of ever-accelerating progress. The following argument is put forth by Ajeya Cotra:

Currently, human researchers collectively are responsible for almost all of the progress in AI research, but are starting to delegate a small fraction of the work to large language models. This makes it somewhat easier to design and train the next generation of models.

The next generation is able to handle harder tasks and more different types of tasks, so human researchers delegate more of their work to them. This makes it significantly easier to train the generation after that. Using models gives a much bigger boost than it did the last time around.

Each round of this process makes the whole field move faster and faster. In each round, human researchers delegate everything they can productively delegate to the current generation of models — and the more powerful those models are, the more they contribute to research and thus the faster AI capabilities can improve (Cotra, 2023).

So before we see a recursive explosion of intelligence, we see a steadily increasing amount of the full RnD process being delegated to AIs. At some point, instead of a significant majority of the research and design being done by AI assistants at superhuman speeds, it will become that - all of the research and design for AIs is done by AI assistants at superhuman speeds.

At this point there is a possibility that this might eventually lead to a full automated recursive intelligence explosion.

The Intelligence Explosion Argument. This concept of the 'intelligence explosion' is also central to the conversation around discontinuous takeoff. It originates from I.J. Good's thesis, which posits that sufficiently advanced machine intelligence could build a smarter version of itself. This smarter version could in turn build an even smarter version of itself, and so on, creating a cycle that could lead to intelligence vastly exceeding human capability (Yudkowsky, 2013).

In their 2012 report on the evidence for Intelligence Explosions, Muehlhauser and Salamon delve into the numerous advantages that machine intelligence holds over human intelligence, which facilitate rapid intelligence augmentation (Muehlhauser, 2012). These include:

- Computational Resources: Human computational ability remains somewhat stationary, whereas machine computation possesses scalability.

- Speed: Humans communicate at a rate of two words per second, while GPT-4 can process 32k words in an instant. Once LLMs can write "better" than humans, their speed will most probably surpass us entirely.

- Duplicability: Machines exhibit effortless duplicability. Unlike humans, they do not need birth, education, or training. While humans predominantly improve individually, machines have the potential to grow collectively. Humans take 20 years to become competent from birth, whereas once we have one capable AI, we can duplicate it immediately. Once AIs reach the level of the best programmer, we can just duplicate this AI. The same goes for other jobs.

- Editability: Machines potentially allow more regulated variations. They exemplify the equivalent of direct brain enhancements via neurosurgery in opposition to laborious education or training requirements. Humans can also improve and learn new skills, but they don't have root access to their hardware: we are just starting to be able to understand the genome's "spaghetti code," while AI could use code versioning tools to improve itself, being able to attempt risky experiments with backup options in case of failure. This allows for much more controlled variation.

- Goal coordination: Copied AIs possess the capability to share goals effortlessly, a feat challenging for humans.